Prelude to a Grift: The Eighties (Part 2)

The era when Elizabeth May worked for Brian Mulroney, which should pretty much tell you everything.

"Wheel of Fortune", Sally Ride, heavy metal suicide Foreign debts, homeless vets, AIDS, crack, Bernie Goetz Hypodermics on the shore, China's under martial law Rock and roller, cola wars, I can't take it anymore" - ‘We Didn’t Start the Fire’, Billy Joel, released September 27, 1989

The first single from his iconic 1989 album Storm Front, Billy Joel’s We Didn’t Start the Fire was a poignant chronology of what Joel, who had just turned 40, considered to be the decline of American culture since the year he was born.

In his review of the album, John McAlley at Rolling Stone wrote, “As the song rushes toward the present, it catalogs the crises that have compromised our dreams.” McAlley also noted that We Didn’t Start the Fire ends in 1989, “with a spirit-crushing litany of contemporary social horrors.”

The “spirit-crushing social horrors” of 1989 seem positively quaint by today’s standards.

The Eighties were frustrating for New Democrats. The party felt cheated out of the 1986 election by a populist Grant Devine, who false-promised his way to a second term, buying Saskatchewan voters with their own money. However, new leadership, to which Roy Romanow was acclaimed in 1987, combined with the brutality of Devine’s second term, brought with it a new sense of optimism for the Saskatchewan NDP.

Once again the next election, to be held in 1991, held promise of NDP victory.

In 1989, George W Bush Sr had just taken the conservative presidential reigns from Ronald Reagan, but the impact of neo-liberalism, promoted by Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, had been significant and far-reaching. Reaganomics in the United States led to tax cuts, reduced welfare spending, and increased military budgets. Similarly, Thatcher's economic policies in Britain aimed to reduce the power of unions and boost industry competitiveness through privatization.

Critics still argue passionately over the fiscal policies of Reagan and Thatcher, with many claiming they exacerbated income inequality, weakened social safety nets and contributed to multiple financial crises.

Grant Devine found both world leaders inspiring, mirroring their policies and attitudes.

Reagan, Thatcher and even Grant Devine, in conjunction with their fiscal policies, proved a stark political contrast to the disintegration of communist strongholds that dominated global affairs during their tenures, particularly after the emergence of the OPEC cartel.

Back in Saskatchewan the mood was light, despite the fact the province’s finances were (somewhat secretly) in a death spiral.

Regina mayor Doug Archer presided over a jubilant Queen City, still riding the high on the Saskatchewan Roughrider’s 1989 Grey Cup win.

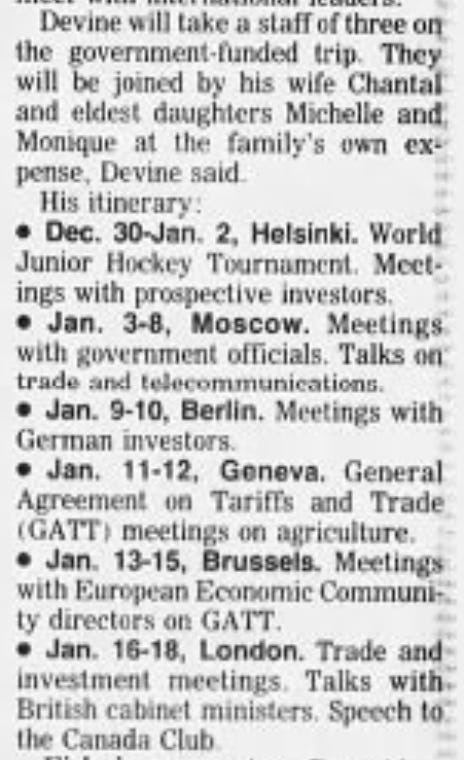

Meanwhile, premier Grant Devine and his family were getting ready for the publicly-funded trip of a lifetime.

Why did the Saskatchewan taxpayer need to finance Grant Devine’s travel to the World Juniors in Finland?

Who cared?

Not Grant Devine.

Because as the thin winter’s light dimmed over a frigid, frustrated Saskatchewan in late 1989, it was clear the people of the province no longer trusted or wanted him as premier. In turn, Grant Devine would go on to show Saskatchewan people how much he didn’t want or need their permission to run this province into the ground.

As you read in the previous chapter, in 1989 Devine and his corrupt caucus had just been shocked by a provincial poll, conducted by and published in the Star Phoenix and Leader Post. The results were decisively, overwhelmingly anti-Devine and anti-PC Party. As was common at the time, broadcast media outlets followed the newspapers’ poll results with their own extensive coverage, meaning anti-Devine sentiment was everywhere.

The cornerstone of Devine’s privatization agenda, the fire sale of SaskEnergy, had just been thwarted by the Saskatchewan NDP and their ongoing protest strike of the Legislature. However, the sale’s death blow was dealt by the same newspaper poll that exposed Devine’s plummeting popularity. It also revealed Saskatchewan people unequivocally wanted to keep the Crown.

So Grant Devine might not have been feeling warm and fuzzy about Saskatchewan, as the plane whisked his family up and away, bound for the Soviet Bloc.

What did Grant ‘Give 'er Snoose’ Devine have to offer the Kremlin in the midst of the Soviet collapse?

Who cared? Not Grant Devine.

In 2024, the most interesting thing about Devine’s 1989 publicly-funded Moscow trip was the number of Saskatchewan journalists who went with him. While they traveled on Devine’s itinerary, their travel expenses were reimbursed by the media outlet.

That practise died long ago in Saskatchewan. The Sask Party has systematically dismantled the mechanisms we once used to hold the government accountable, including how it interacted with media. The second reason was cash-strapped, budget-slashed newsrooms ran out of money to pay for it.

In the Eighties and Nineties, Saskatchewan voters wanted, expected and received far more information, from both the media and provincial government, than they get today.

Even after reluctantly agreeing to reduce it from nine to seven percent, as the Nineties loomed, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney could not appease Canadians outraged over his incoming Goods & Services Tax (GST).

John Turner was in his final days as leader of the federal Liberal party. Audrey McLaughlin had just replaced Ed Broadbent as leader of the federal NDP. Broadbent would go on to be appointed, by Mulroney, as the president of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development.

Back then, federal leaders weren’t petty bitches.

Not all the time, anyway.

Mulroney was less likely to show diplomacy on the construction of the Rafferty-Alameda dam.

In February 1986, Premier Grant Devine met with American politicians, formally kicking off the project, managed jointly between Canada and the US. The dam was North Dakota’s idea, blaming Canada for flooding woes in the state. The benefit to the province, claimed the provincial government, was the dam would provide water for irrigation (in certain ridings, coincidentally, big supporters of Devine’s party) and as coolant for Sask Power’s new Shand power plant.

Not that Devine had to be convinced. Rumors of the project caused land prices in the riding of PC Party MLA, senior cabinet minister and bargain bin-Dick Cheney, Eric Berntson, to skyrocket.

They also caused outrage.

Publicly, the details were murky. Pundits, the Saskatchewan NDP Opposition and newspaper editorials demanded more information; a cost/benefit analysis, for example. Devine would only state, vaguely, that taxpayers would be out between $100 and $200-million on the dam’s construction.

That’s a huge, reckless unknown gap; in today’s dollars, between a quarter and a half-billion.

Ranchers who grazed cattle upstream from the Rafferty-Alameda site were furious at the prospect of losing land, accusing the premier of putting his relationship with America before Saskatchewan people. Environmentalists lost their minds over the potential loss of thousands of acres of wetlands and the annihilation of fragile prairie ecosystems.

A string of legal and political challenges, launched by those groups and others, plagued Devine’s PC Party government and the dam project throughout its construction.

Devine forged ahead regardless.

“In government, you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t, so we’re going to dam it anyway,” boasted Devine, evoking one of his beloved, folksy tropes, in a speech he cheerfully delivered as controversy over the project raged.

The federal license for the Rafferty-Alameda project was issued by the Mulroney government in June 1988, not that its absence had been holding anything up. The Devine government had commenced construction of the dam months earlier without one, on a wink and a nod from Mulroney that there would be no consequences.

September 1988: a fiesty, fresh-faced staffer from the federal Ministry of Environment burst into the news, alleging the Rafferty-Alameda licensing process was a farce.

A senior policy advisor to Mulroney’s federal Minister of Environment, Elizabeth May, 34, charged that backroom conservative operatives from Ottawa and Saskatchewan struck a deal to circumvent Canadian law. She alleged that instead of environmental protocols and assessments pre-empting the license, political favours had been exchanged between Devine and Mulroney.

May’s disclosure prompted the United States government to pause funding their side, at least until environmental issues were sorted out. A month later, November 1988, the Canadian Wildlife Foundation (CWF) launched its lawsuit against the project, adding to a growing list.

May resigned from Mulroney’s government. A year later she helped launch the Sierra Club.

In the spring of 1989, a Canadian federal court justice revoked the license for the construction of the Rafferty-Alameda dam, over environmental infractions. In the fall, the Mulroney government reinstated it. What ensued was a dog’s breakfast of jurisdictional bureaucracy, overreach and outright law-breaking.

In all this, a historical development. As the Eighties were slinking off the stage, Canadian courts recognized, for the first time and in a ruling against Saskatchewan, that federal environmental guidelines were legally binding.

As part of that ruling, three days before New Year’s, a judge ordered more environmental-protocols for the dam. Construction would need to be paused, again. After months of wild instability, the judgment left workers to face the New Year and the Nineties with their income, just like the dam’s future, up in the air.

They’d be comforted soon enough, because Grant Devine, as he faced an existential threat to his tenure in the premier’s office, would bulldoze anything, including federal laws.

25 years after Rafferty-Alameda was built, in 2011, North Dakota would experience one of the worst floods in its state history.

On December 6, 1989, a misogynist walked into Montreal's École Polytechnique and fatally shot 14 young women, just because they were women. Technically this was one of the world’s first school shootings, before the term “school shooting” became part of the lexicon of daily life. A few years later, Columbine would sew up that dubious distinction.

Brutal violence was rocking countries involved in regional conflicts across the world, from Romania to Panama. Nelson Mandela was still in prison, on the verge of release.

Meanwhile, as he was actively destroying hundreds of acres of farmland by Estevan, Grant Devine was threatening the country that “time was running out” for Saskatchewan’s ag industry. Poor to fair crops had brought in low prices that year. Yet, despite Devine’s demand for $500-million from the feds, Mulroney said prices weren’t low enough to send a stabilization payment.

Saskatoon, under relative newcomer mayor Henry Dayday, had the second highest unemployment rate in Canada at 10 per cent. Molson’s Brewery, a critical local job creator, was about to be sold to a group of its employees.

On December 30, 1989, this blurb ran on the cover of the Star Phoenix’s free, home-delivered spinoff product, the Prism.

Spoiler alert: it wasn’t.

As the faint new light of the Nineties dawned, Saskatchewan moviegoers, including those in the many rural cities and towns that still had a functioning theatre, were blessed with quality and choice (though this may not have been as apparent at the time). Cinematic offerings of the day included Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing; Drugstore Cowboy; My Left Foot; Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade marked the third installment in the franchise; Batman; When Harry Met Sally; Driving Miss Daisy; Born on the Fourth of July; Steel Magnolias; sex, lies and videotape and The Fabulous Baker Boys.

Perhaps Dick Spencer, a longtime conservative architect, former campaign strategist for John Diefenbaker, mayor of Prince Albert and apologist for Grant Devine, best summed up the mood as Saskatchewan entered the Nineties and the final years of Devine’s last term:

“(Devine and his MLAs) knew the economy, much of it was beyond their control, was in shambles, and that many of their high-priced promises could not be kept. They knew their deception about the 1986 budget deficit would be exposed and the provincial debt would continue to climb dangerously… They knew they were now being scrutinized by a wary public and a cranky media. They knew the business community was uneasy, the labour leadership hostile and the provincial civil service disoriented.

Yet, in desperation, perhaps in colossal näiveté, they pushed on to rescue the economy and themselves with neo-conservative schemes of privatization and experiments in decentralization that would not work.” - Dick Spencer, Singing the Blues: The Conservatives in Saskatchewan (U of Regina, 2007).

If that’s what Devine’s friends had to say about the end of the Eighties, it’s safe to say the reality was worse.

Let’s also not forget that while Devine’s caucus was pushing to “rescue… themselves with neo-conservative schemes”, many of the MLAs in it were wilfully, deliberately and criminally stealing from Saskatchewan people and their government.

With that, we leave the Eighties to march into the Nineties, a decade that is typically pulled apart, dissected and reassembled in the image of whoever you’re talking to at the moment.

For some, the Nineties marked a time where leaders put province before party and made difficult but necessary decisions. Others feel the Nineties was the decade that killed what Saskatchewan could have been, devastating rural communities with healthcare and education cuts that were rooted in partisanship, not fiscal necessity.

What’s undeniable is the Nineties were pivotal in creating the Saskatchewan that has unfolded around us today. Understanding how previous Saskatchewan leaders and voters navigated crises or implemented successful reforms can inspire us to emulate their successes or learn from their failures. In essence, examining the facts about Saskatchewan’s political past not only helps us gain a deeper appreciation of where we come from, but also serves as a roadmap for charting a more informed and sustainable course towards a brighter future.

Consider this book akin to going through old photos from that questionable phase in high school — sure, it may be cringe-worthy, but it also helps us see how far we've come and what we don't want to do over.

See you in 1990, or Chapter 1.

What a great article. So well written! Loved all the cultural references. Helps situate that point in time. There's definitely a book here, Tammy. Brava as usual.