Prelude to a Grift: The Eighties (Part 1)

They were the best of times, they were th-... welll, they were just really bad.

As we take this journey back in time together, you’re going to see that the Saskatchewan RCMP likely did not have the capacity to properly and thoroughly investigate the sheer volume of criminality that defined Grant Devine’s time as premier.

As the Eighties drew to a close, behind the scenes there was so much stolen money flying around the PC Party caucus office in the Saskatchewan Legislature that John Scraba, Devine’s communication director, couldn’t fit the thousand dollar bills in his desk anymore.

He was having trouble finding places to put it.

The plan that resulted in Scraba holding stacks of taxpayer’s cash was hatched at a PC Party caucus retreat in Cypress Hills in March of 1987, or about six months after Devine’s government was re-elected.

At that retreat, Devine’s caucus agreed to pool 25 percent of their publicly-funded individual communications allowances into one central fund, under the guise of increased buying power for caucus advertising.

Scraba would later testify that, at the same retreat, PC Party MLAs Lorne McLaren (Yorkton, Minister of Labour), John Gerich (Redberry, Brad Wall’s boss at the time), Michael Hopfner (Cut Knife-Lloydminster) and Sherwin Petersen (Kelvington-Wadena, Minister of Highways) also directed him to set up three numbered companies, each with a correlating bank account.

“The three companies were nothing more than vehicles for moving money. They had no assets, no staff, no equipment, no business office, and no line of credit. What each did have was a bank account for such was essential in order to carry out the function for which they had been created. Each company also had printed invoices bearing its name.” - R. v. Berntson, 1999 CanLII 12472 (SK KB), para 39

The “function”, for which those companies and their associated bank accounts had been created, of course, was fraud.

The process was simple.

If a PC Party MLA wanted cash, Scraba would generate a fake invoice from one of the shell companies, then have it signed off by the corrupt MLA as an expense. The paperwork was submitted to the Legislature, where it would be approved by the clerks working in the finance department.

From there payment, by cheque, was sent to the mailing address of the PC Party’s law firm in Regina (which claimed ignorance of the scheme). Scraba would pick up and deposit the cheque into the shell company’s bank account, wait for it to clear, withdraw the cash and funnel it back to his colleagues, or the PC Party itself.

After two years of orchestrating a white collar fraud ring, backed by members of Grant Devine’s innermost circle, Scraba’s desk in the bowels of Saskatchewan Legislature was literally overflowing with thousand dollar bills.

Perhaps sensing staff in the finance department might be getting suspicious of the neverending ream of invoices coming in from the same three communications companies, by the end of 1989, Scraba was getting set to incorporate yet another - a fourth - numbered company.

Meanwhile, staff at the Legislative Assembly’s finance department were getting suspicious of the neverending ream of invoices coming in from the same three communications companies.

In late 1989, Legislative Assembly clerk Gwenn Ronyk, uncomfortable with the way PC Party caucus money was moving, took her concerns over it to PC Party Speaker Arnold Tulsa.

Gwenn Ronyk would eventually become the catalyst for the launch of the RCMP investigation into Grant Devine’s caucus. It was not to be that day in 1989, however, because Speaker Tulsa outright dismissed her concerns.

It was just the way things were done, he said.

Tulsa wasn’t wrong.

It would come to light in hindsight, as it so often does, that the communications fraud scheme wasn’t the first time the PC Party misappropriated public money.

After winning a landslide fifty-five Legislative seats in 1982, a pile of public operating cash from the Saskatchewan Legislature poured into Devine’s caucus office.

On December 6, 1985, during Devine’s first term, $450,000 of that public money was quietly stolen from the PC caucus’s bank account and transferred into a secret, private bank account opened in Martensville by veteran PC MLA Ralph Katzman (Rosthern).

A good chunk of that $450,000 was used, illicitly, by the PC Party, to conduct polling in advance of the 1986 Saskatchewan election.

$45,000 of it was given to PC Party caucus chairman Lorne McLaren (Yorkton), allegedly at the direction of Grant Devine, who has always denied having any knowledge of the fraud, the secret bank accounts or anything else.

At Katzman’s trial, well over decade later, we learned that by December 1986, the PCs had drained their own bank accounts dry to win that second term. Put simply, the party was broke.

In January of 1987, another $125,000 in public money was transferred from the PC Party caucus to a private PC Party bank account. A decade later, disgraced former PC Party cabinet minister and federal Conservative Party of Canada senator Eric Bernston would be tried for breach of public trust for that one, but unlike his conviction for fraud, that count would not hold up in court.

In the Eighties, caucus bank accounts that received public funding from the Saskatchewan Legislature weren’t audited. Political parties and individual politicians elected to form government were presumed to be honourable.

As the Eighties drew to a close, three very different, fierce leaders stood poised to fight for the next Premier’s seat.

On April 2, 1989, Lynda Haverstock replaced Ralph Goodale as Saskatchewan’s provincial Liberal party leader. She won on the first ballot over two other candidates, including the former president of the province’s SUN nurses’ union.

Haverstock was merely a regional party volunteer when approached by Liberal Party operatives in September of 1988 about pursuing the leadership. After some serious courting, led by prominent Saskatchewan businessperson Neil McMillan, Haverstock agreed to let her name stand.

One of her stipulations for her candidacy, was that Haverstock, a practising clinical psychologist, would not cancel any of the dozens of farm stress workshops she had booked across Saskatchewan, in order to run the party.

Haverstock, a charismatic and dynamic figure, brought a fresh perspective to the political landscape and challenged the dominance of the Saskatchewan New Democratic Party (NDP) and the Progressive Conservative (PC) Party.

She advocated for a pragmatic approach to governance, emphasizing issues such as healthcare, education, economic development, and social welfare. Haverstock focused on promoting sustainable economic growth, improving access to healthcare services, and supporting small businesses and rural communities.

Her policies resonated with a broad spectrum of voters, appealing to those seeking a middle-ground alternative to the NDP and PC Party platforms.

“I don’t want to be known as a typical politician… someone who will govern and will be part of developing something in this province that will give a new definition to what a politician is all about.

I desire to cross all political lines.”

- Lynda Haverstock, April 4, 1989 Saskatoon Star Phoenix

Unfortunately for Lynda and despite the fact she would secure a quarter of the provincial vote in her first election as Liberal leader, political success was not in her cards. In fact, some of what lied ahead for her after winning the Liberal leadership was personally traumatic, terribly unfair and would change both her life and the face of Saskatchewan politics forever.

In 2001, in a piece she wrote for Howard Leeson’s first Saskatchewan Politics anthology, Haverstock described the Liberal Party she’d led til 1995 as in “a perpetual state of self-annihilation”.

Regardless, while Haverstock faced challenges and setbacks during her political career, including electoral defeats and internal party dynamics, her perseverance and dedication to public service left an indelible mark on Saskatchewan’s political history.

As the first woman to lead a major political party in the province, 40-years-old and a single mom, Haverstock broke barriers and inspired a new wave of support for Saskatchewan Liberals.

It wasn’t easy, to be clear.

“Former leaders, some of whom had been considerably younger than (I), had never been described physically in newspaper articles nor was it implied that they were “too young” for the job,” Haverstock wrote in 2001, of her experience as Liberal Party leader.

Eventually, she came to view the media and her political colleagues making incessant references to her age and appearance for what it was: paternalistic and gender discriminatory.

As soon as she was installed as the party’s leader, Haverstock says the same Liberals who talked her into taking the job went “missing in action”. Promises made regarding her salary were abandoned, forcing her to remortgage her personal residence in order to just get by.

Yet under her leadership, the Liberal Party saw increased membership, improved organization, and a reinvigorated presence in the Saskatchewan political arena.

That’s likely why, in a pattern that still holds today, the PC Party would go on to launch vicious personal attacks on Haverstock, including a five-page circular that thoroughly, misogynistically degraded her profession, her politics and her personal life.

We’ll look more at that horrific document - and who wrote it - when we hit 1991.

Lynda Haverstock’s leadership, policies, and personal attributes helped to shape the political landscape of the province, and her legacy continues to resonate with those who value inclusivity, progressivism, and a commitment to democratic principles.

Haverstock's ability to engage with voters, communicate effectively, and build strategic alliances within the Liberal Party of Saskatchewan helped to strengthen its credibility… something MLA Bill Boyd and his PC Party would soon one day need for themselves, desperately.

The Saskatchewan NDP’s leader, Roy Romanow, was installed by the party in 1987 to replace Alan Blakeney.

The Saskatchewan NDP, under the leadership of Premier Allan Blakeney, had championed social justice policies, advocating for accessible healthcare and education and the preservation of crown corporations. However the party had also faced challenges, such as economic recession and public opposition to its left-leaning policies, which had led to decline in public support and internal conflict in Blakeney’s party.

1987 was the second time Romanow, who had been first elected as the NDP MLA for Saskatoon Riversdale in 1967, had contested the NDP leadership. He was an ambitious 30-year-old when he ran the first time (and almost won) in 1970 to replace Woodrow Wilson, then held a relatively high profile in Saskatchewan as deputy premier for over a decade. Romanow played a significant role in the patriation of the Canadian constitution and the creation of Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The evolution of broadcast communications and print media in the Eighties increased our exposure, even way up in Saskatchewan, to television, movies and music. Celebrities and public figures grew more glamorous and more outrageous, yet also more mainstream.

By the time he was installed as Saskatchewan’s NDP leader in 1987, Roy Romanow was a sophisticated, polished and distinguished 48-year-old politician. A ruggedly handsome son of Slavic immigrants, Romanow was referred to in certain Baba’s circles as a “Ukrainian Robert Redford”.

In true Dipper fashion, a faction of the party was unimpressed.

As Janice MacKinnon wrote in her 2003 book, Minding the Public Purse, after Romanow was elected, one of his problems was, well, his own party.

“…many New Democrats harboured suspicions that Romanow himself was a closet Liberal. Never known as a party man or a union guy, Romanow dressed well and spoke moderately — further causes for suspicion by some on the left.” - Janice MacKinnon, Minding the Public Purse (2003)

He did know how to dress well.

In a piece he wrote for the University of Regina’s Crowding the Centre (Leeson, 2008), Romanow explained how, as Opposition leader in the late Eighties, he fully grasped the rapidly increasing power of personal image and the media, when appointing members of his caucus to their critic portfolios.

“I was looking for men and women who could credibly stand up in the House, pose the questions or make the appropriate statements… I was also looking for them to be able to communicate our core messages to the journalists…” - former Saskatchewan Premier Roy Romanow, Crowding the Centre (Leeson, 2008)

“The decade of the 1980s had been a frustrating one for New Democrats,” wrote Howard Leeson in his 2001 book, in an introductory essay entitled The Rich Soil of Saskatchewan Politics.

“Feeling cheated out of victory in 1986…they could only sit by helplessly and watch as the Conservatives attempted to dismantle much of what the CCF/NDP had put in place over the previous four decades. But with the election of Romanow as leader, optimism began to return to the party.”

With everything he’d already accomplished in his back pocket, at the end of the 1980s, Roy Romanow’s greatest challenge and the defining moments of his career still lied ahead.

Grant Devine deserved to win the 1986 provincial election about as much as Ben Johnson deserved to win the gold medal in 1988.

However, Devine’s folksy charm, political promises and outright rural Saskatchewan vote-buying with taxpayers’ money also proved a powerful drug. All played a role in securing him a second term as Premier.

“You love the sinner but you hate the sin,” then-premier Grant Devine told reporters in March of 1988, after NDP MP Svend Robinson’s historical admission that he was a gay Canadian parliamentarian.

“I feel the same about bank robbers…”

As one of Brad Wall’s final acts of political patronage, Grant Devine sits on the University of Saskatchewan board of governors today. Devine has never been asked to reconcile his very public, very bigoted statements on homosexuality.

I have questions about USask’s participation in Pride Month festivities in 2024, while remaining silent regarding this incredibly shameful historical episode within their own leadership.

But I digress.

With the Nineties on the horizon, an overconfident and seemingly manic Grant Devine was in his second and clearly final term as premier.

By 1989, Devine’s appetite for running up reckless public tabs had become insatiable.

Accountability for his behaviour and that of his caucus was non-existent.

“…the significant hallmark of the Progressive Conservative government lay in its belief that simply because it held a majority of the seats in the Legislative Assembly it could do whatever it wanted. (Devine’s) government demonstrated this attitude in its cavalier approach to the legislature and to formal demands for executive accountability.”

- Merrilee Rasmussen, The Role of the Legislature, Saskatchewan Politics Into the 21st Century (Leeson 2001)

After carving up and selling off a number of valuable Saskatchewan crown assets, a tipping point had been reached when Devine and his party tried to do the same with SaskEnergy in 1989.

With a fired-up Opposition leader Roy Romanow at the helm, the NDP caucus refused to enter the Assembly when the bell rang, at which they were to debate the SaskEnergy sale bill. A Legislative walk-out by the Opposition ensued, earning overwhelming support from the Saskatchewan public, despite Devine’s frantic efforts to frame the NDP’s actions as an affront to democracy.

The NDP’s rebellion, which lasted for weeks, was bolstered by a public petition that circulated the province with over 100,000 signatures, demanding Devine kill the sale.

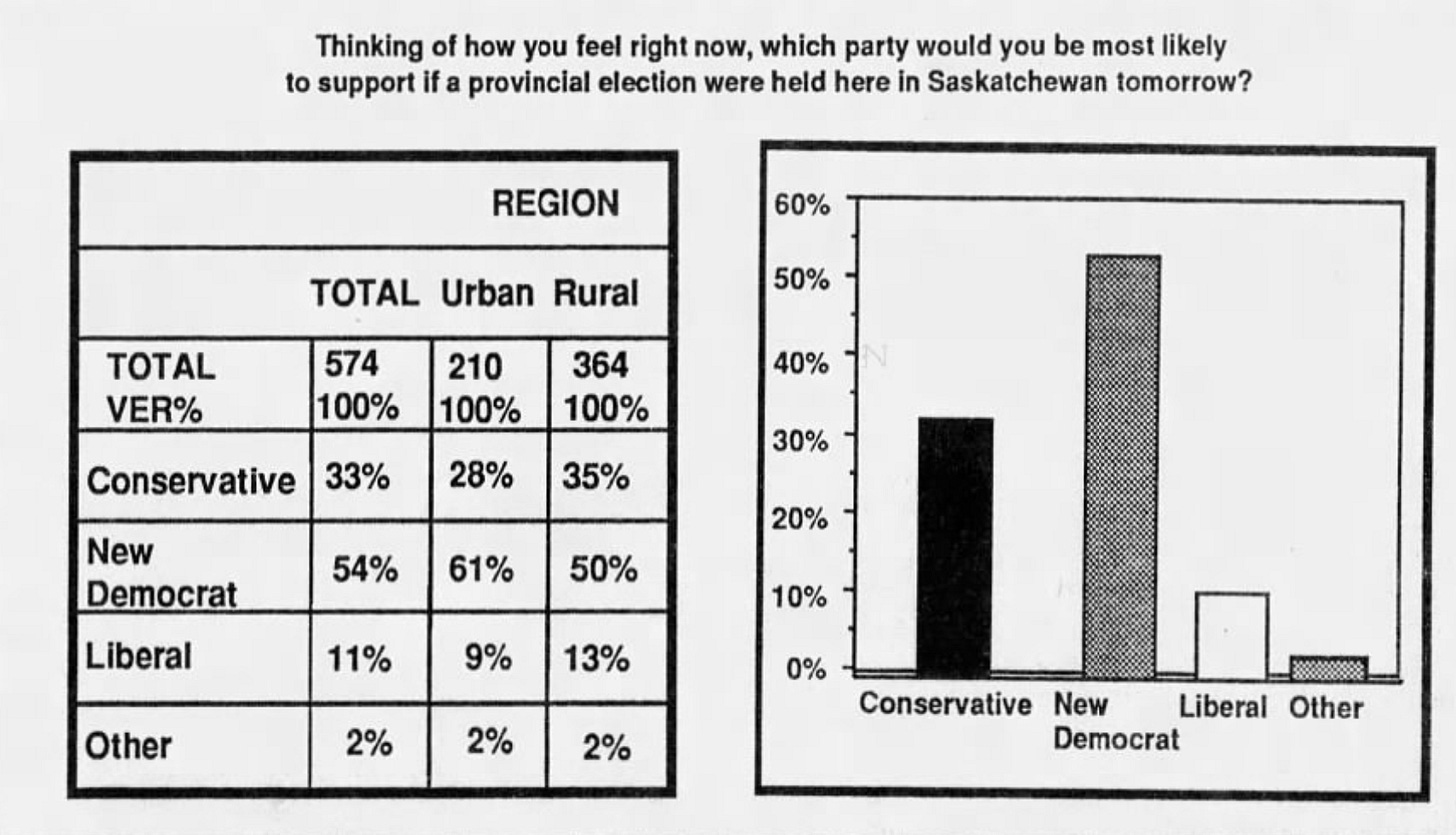

Perhaps the most significant damage to Devine’s plan for SaskEnergy was done by devastating public poll results on the issue, which were published in the Saskatoon Star Phoenix and Regina Leader Post in May of 1989.

A short time later, Devine was forced to pull the sale off the table. The sting of the reality that had been revealed by those polling results, however, lingered.

As the Eighties wrapped in Saskatchewan, Grant Devine knew that as the province’s premier, his time was up.

That he no longer held the support of anything resembling a majority of Saskatchewan people.

Yet Grant Devine chose to stay in the premier’s office until 1991. Under his leadership, the province’s finances were wilfully mismanaged and almost completely bankrupt.

Rather than addressing mounting deficits or making difficult fiscal choices, Devine drained public coffers, perpetrating a vicious cycle of spending and borrowing. Reactionary, expensive patchwork policies helped his government cling to power in the short term, but accelerated Saskatchewan’s inevitable descent into long term economic ruin.

Meanwhile, his caucus was stealing staggering amounts of taxpayers’ dollars, right from under his nose.

As the PC Party government’s second term took off, public money was flying out the Legislature’s front door into rural Saskatchewan and out the back door via the briefcases of Devine’s caucus members.

One MLA would later testify at her trial that she stole $5000 to take a trip to Hawaii out of spite, because Devine dropped her from cabinet.

In the Eighties, MTV was in its infancy, but would become one of the primary drivers of Westernized culture. At the same time, the concept of reality was still largely grounded in physical presence — a state of being, not an entertainment genre.

Defined by bad hair, worse fashion and cell phones the size of a loaf of bread, the Eighties in Saskatchewan, like everywhere else in North America, was a big, brash and bizarre decade. It was a time that highlighted, with brutal precision and clarity, the ideological differences between Saskatchewan's political parties and by extension, its people.

The NDP spent the decade emphasizing social justice and welfare, the PC Party prioritizing economic growth and social conservatism, while the Liberal Party claimed to offer alternative perspectives to both.

As it wrapped, Saskatchewan men who are still today, incomprehensibly, controlling the Sask Party, were just little boys getting their feet wet as staffers in Devine’s Legislature.

Many would go on to dedicate their careers to manipulating and personally profiting off the province of Saskatchewan and the people who built it.

Turns out, it only takes a handful of greedy, petty backroom operatives to obliterate the proud, multi-generational history of pioneering a western province.

We’ll be talking about them too.

In Part 1 of this Prelude, we’ve scanned the political environment of the 1980s in Saskatchewan.

In Part 2, the final part before we crossover into the Nineties, we’ll look at the people and culture of Saskatchewan during the Eighties, including what drove voters (and which voters) to re-elect a flailing Grant Devine.

Til then,

Thanks for reviewing these events!