I’ll update (but won’t email) the copy here, every time I publish a new chapter, if you’d prefer to read it all in one place. Bookmark this link if it’s more convenient for you.

Remember, this is a separate product from my other Substack (Our Sask). It’s a labour of love and I would be thrilled if you joined us.

The Nineties In Saskatchewan: An Introduction

On the vast expanse of the Canadian Prairies lies a province with a rich and storied history – Saskatchewan.

The modern history of the province that’s hard to spell but easy to draw is embryonic. We’ve got a handful of decades under our belt. This, compared to the thousands of years of recorded history of places like Europe and Asia, where the political seeds of the Western world and eventually, Saskatchewan, were germinated.

A land of breathtaking landscapes, resilient communities, intricate political dynamics and Tommy Douglas’s Medicare, Saskatchewan emerged again as a focal point of Canadian politics in the 1990s, though at times for the wrong reasons. It was a time of profound change, as the province navigated economic uncertainty, the unraveling of government criminality, political upheaval and social transformation.

Like many of you, I was a teen in Saskatchewan in the Nineties. My interests were Pearl Jam, Party of Five, flannel shirts and baby doll dresses.

I wasn’t paying attention to what was happening with the government.

If you are any kind of politics watcher today, you might even know the exact number of Saskatchewan schools and hospitals closed by the Saskatchewan NDP in the Nineties (52). The vast majority of those closures were in rural Saskatchewan, generating a bitterness towards the NDP that still wafts through its wide open spaces today.

However, that’s where the tale of the Nineties often begins and ends — and that’s a problem.

Those hospital and school shutdowns played out alongside a parade of criminal courtroom dramas involving Devine’s cabinet ministers and MLAs, as well as backroom operators who are still, inexplicably, working in the Legislature with the Sask Party today.

When Grant Devine took office, Saskatchewan’s finances were fantastic. He went on to deliver consecutive deficit budgets and drastically increased spending, including on money-losing megaprojects and corporate subsidies.

Over the course of a decade, Saskatchewan's debt grew from $3.5-billion in 1982 to $15-billion in fiscal year 1991–1992. That’s almost $30-billion in 2024 dollars.

Far worse, by 1991 the province’s annual interest payments had exceeded $500-million and were the third largest line item in the provincial budget after health and education.

As the 90s dawned, Saskatchewan was virtually bankrupt.

It was also a hotbed of social movements and cultural expressions. Indigenous rights activism, environmental advocacy, and LGBTQ+ rights campaigns gained momentum, challenging the mainstream discourse and pushing for a more inclusive and equitable province.

As we delve deeper into the intricacies of Saskatchewan politics in the 1990s, we are confronted with a narrative that was both unique to the province and reflective of broader trends in Canadian society. The legacy of this transformative decade continues to reverberate in the debates, decisions and dynamics of contemporary Saskatchewan.

Its legacy can’t be properly defined, however, until the historical narrative is corrected, both through retellings like this one and hopefully more down the road.

Even though the facts on the Nineties are well recorded in solid sources like the Legislative Assembly Hansard and thousands of archived news stories, they have also become almost wholly subjective to the storyteller. The truth has been obscured by rhetoric to the point that the narrative has become accepted as factual.

Saskatchewan was on the brink of receivership. Yet the fiscally-necessary school and hospital closures are what have captured our attention and emotions.

What will follow this Introduction is a chronological, fact-based reconstruction of what happened in Saskatchewan politics in the Nineties. Should you choose to subscribe, together we’ll examine the events that greatly impacted the trajectory of each political party in Saskatchewan and by extension, the province itself, as they were happening both behind closed doors and in the public eye.

Then you can decide the truth about Saskatchewan in the Nineties.

Nobody’s here to demonize Grant Devine and his government, but it’s no spoiler alert that the facts on what happened are simply appalling. It is shocking that a politician and leader as inept as Devine, regardless of what he did or didn’t know about the criminality under his nose, has been embraced and welcomed back into the fold by any political party.

This is also not about vindicating Roy Romanow and his government. Same principle applies - the facts will speak for themselves. It’s just a damn shame that Romanow and his party went out of their way to not share those facts with you. There was a toxic arrogance behind Romanow and his party’s refusal to explain their decisions, seemingly driven by the notion that Saskatchewan people knew Grant Devine was fiscally reckless, but voted for him for a second term anyway.

One thing that may become abundantly clear, by the time you’re finished reading this series, is that since Tommy Douglas, the Saskatchewan NDP have not been able to communicate effectively with the people of this province.

An examination of the Nineties in Saskatchewan raises questions about why the province is where it is today.

Why did the Saskatchewan NDP allow their own party history to be appropriated and rewritten by their political opponent?

Who started the hyperbolic and often misleading school and hospital closure narrative, when and why?

How bad were Saskatchewan’s finances in the Nineties, really?

Why was the Saskatchewan media unable to uphold the public record?

Was the Saskatchewan Party born from necessity, or was it simply a vehicle created to save Bill Boyd’s political career?

This work is not based on a whole bunch of one-on-one interviews and eyewitness accounts. As we’ll learn at more than a few stops over the course of this journey, pretty much everyone involved in the Nineties in Saskatchewan has had plenty of opportunities to be heard.

Problem is, they’re often telling different stories.

I have interviewed Lynda Haverstock extensively over the years and drawn greatly from those conversations — I may even share some of the audio. I’ve interviewed other players from that era, including former Devine and Romanow cabinet ministers… who, even today, don’t want to be named.

The Nineties were a brief but golden age in journalism in Saskatchewan, so this series draws heavily from the archives of the Saskatoon Star Phoenix, Regina Leader Post and CBC Saskatchewan. Each of those newsrooms enjoyed a roster of dozens of journalists, with multiple individuals covering the Saskatchewan Legislature.

I have written and compiled this information over the course of the last ten years. The purpose was once a book; in fact, circa 2017 I was in discussions with editors and publishing houses about going down that road.

I walked away from it.

Let’s just say the process was severely tainted for me, rightly or wrongly, by what I was experiencing in Saskatchewan, at the hands of many of the same people who stood to be rather embarrassed by the contents of what I will publish.

It needs to be released, however. It’s weighing me down.

The first chapter is titled Prologue: The Eighties, from there we’ll start with Chapter 1: 1990. Most years will be split into two chapters and my goal is to publish a new chapter every two to three weeks. The majority of the writing is already done, but I’ll be refining it along the way.

My hope for readers of this new publication is that you come away from this exercise with a new, in-depth understanding of an era in Saskatchewan that was as dramatic, complex and nuanced as it was stupid.

I also hope you’re entertained, because it’s a story that is, at least at times, comedic in its buffoonery.

Mindblowing in its audacity.

Nauseatingly greedy.

It is a tale that is maddeningly, scandalously and boldly corrupt.

Above all, it is one that is quintessentially Saskatchewan: driven by a tiny population, no degrees of separation and a political culture entrenched in fear and insecurity.

The Nineties were pivotal, complex and nuanced, like virtually every other decade of the few Saskatchewan has under its belt. However, they were also strikingly simple in so many ways, particularly when compared to the vitriolic, complex and destructive environment in the Saskatchewan Legislature today.

I hope you enjoy it.

Prelude to a Grift: The 80s (Part 1)

As we take this journey back in time together, you’re going to see that the Saskatchewan RCMP likely did not have the capacity to properly and thoroughly investigate the sheer volume of criminality that defined Grant Devine’s time as premier.

As the Eighties drew to a close, behind the scenes there was so much stolen money flying around the PC Party caucus office in the Saskatchewan Legislature that John Scraba, Devine’s communication director, couldn’t fit the thousand dollar bills in his desk anymore.

He was having trouble finding places to put it.

The plan that resulted in Scraba holding stacks of taxpayer’s cash was hatched at a PC Party caucus retreat in Cypress Hills in March of 1987, or about six months after Devine’s government was re-elected.

At that retreat, Devine’s caucus agreed to pool 25 percent of their publicly-funded individual communications allowances into one central fund, under the guise of increased buying power for caucus advertising.

Scraba would later testify that, at the same retreat, PC Party MLAs Lorne McLaren (Yorkton, Minister of Labour), John Gerich (Redberry, Brad Wall’s boss at the time), Michael Hopfner (Cut Knife-Lloydminster) and Sherwin Petersen (Kelvington-Wadena, Minister of Highways) also directed him to set up three numbered companies, each with a correlating bank account.

“The three companies were nothing more than vehicles for moving money. They had no assets, no staff, no equipment, no business office, and no line of credit. What each did have was a bank account for such was essential in order to carry out the function for which they had been created. Each company also had printed invoices bearing its name.” - R. v. Berntson, 1999 CanLII 12472 (SK KB), para 39

The “function”, for which those companies and their associated bank accounts had been created, of course, was fraud.

The process was simple.

If a PC Party MLA wanted cash, Scraba would generate a fake invoice from one of the shell companies, then have it signed off by the corrupt MLA as an expense. The paperwork was submitted to the Legislature, where it would be approved by the clerks working in the finance department.

From there payment, by cheque, was sent to the mailing address of the PC Party’s law firm in Regina (which claimed ignorance of the scheme). Scraba would pick up and deposit the cheque into the shell company’s bank account, wait for it to clear, withdraw the cash and funnel it back to his colleagues, or the PC Party itself.

After two years of orchestrating a white collar fraud ring, backed by members of Grant Devine’s innermost circle, Scraba’s desk in the bowels of Saskatchewan Legislature was literally overflowing with thousand dollar bills.

Perhaps sensing staff in the finance department might be getting suspicious of the neverending ream of invoices coming in from the same three communications companies, by the end of 1989, Scraba was getting set to incorporate yet another - a fourth - numbered company.

Meanwhile, staff at the Legislative Assembly’s finance department were getting suspicious of the neverending ream of invoices coming in from the same three communications companies.

In late 1989, Legislative Assembly clerk Gwenn Ronyk, uncomfortable with the way PC Party caucus money was moving, took her concerns over it to PC Party Speaker Arnold Tulsa.

Gwenn Ronyk would eventually become the catalyst for the launch of the RCMP investigation into Grant Devine’s caucus. It was not to be that day in 1989, however, because Speaker Tulsa outright dismissed her concerns.

It was just the way things were done, he said.

Tulsa wasn’t wrong.

It would come to light in hindsight, as it so often does, that the communications fraud scheme wasn’t the first time the PC Party misappropriated public money.

After winning a landslide fifty-five Legislative seats in 1982, a pile of public operating cash from the Saskatchewan Legislature poured into Devine’s caucus office.

On December 6, 1985, during Devine’s first term, $450,000 of that public money was quietly stolen from the PC caucus’s bank account and transferred into a secret, private bank account opened in Martensville by veteran PC MLA Ralph Katzman (Rosthern).

A good chunk of that $450,000 was used, illicitly, by the PC Party, to conduct polling in advance of the 1986 Saskatchewan election.

$45,000 of it was given to PC Party caucus chairman Lorne McLaren (Yorkton), allegedly at the direction of Grant Devine, who has always denied having any knowledge of the fraud, the secret bank accounts or anything else.

At Katzman’s trial, well over decade later, we learned that by December 1986, the PCs had drained their own bank accounts dry to win that second term. Put simply, the party was broke.

In January of 1987, another $125,000 in public money was transferred from the PC Party caucus to a private PC Party bank account. A decade later, disgraced former PC Party cabinet minister and federal Conservative Party of Canada senator Eric Bernston would be tried for breach of public trust for that one, but unlike his conviction for fraud, that count would not hold up in court.

In the Eighties, caucus bank accounts that received public funding from the Saskatchewan Legislature weren’t audited. Political parties and individual politicians elected to form government were presumed to be honourable.

As the Eighties drew to a close, three very different, fierce leaders stood poised to fight for the next Premier’s seat.

On April 2, 1989, Lynda Haverstock replaced Ralph Goodale as Saskatchewan’s provincial Liberal party leader. She won on the first ballot over two other candidates, including the former president of the province’s SUN nurses’ union.

Haverstock was merely a regional party volunteer when approached by Liberal Party operatives in September of 1988 about pursuing the leadership. After some serious courting, led by prominent Saskatchewan businessperson Neil McMillan, Haverstock agreed to let her name stand.

One of her stipulations for her candidacy, was that Haverstock, a practising clinical psychologist, would not cancel any of the dozens of farm stress workshops she had booked across Saskatchewan, in order to run the party.

Haverstock, a charismatic and dynamic figure, brought a fresh perspective to the political landscape and challenged the dominance of the Saskatchewan New Democratic Party (NDP) and the Progressive Conservative (PC) Party.

She advocated for a pragmatic approach to governance, emphasizing issues such as healthcare, education, economic development, and social welfare. Haverstock focused on promoting sustainable economic growth, improving access to healthcare services, and supporting small businesses and rural communities.

Her policies resonated with a broad spectrum of voters, appealing to those seeking a middle-ground alternative to the NDP and PC Party platforms.

“I don’t want to be known as a typical politician… someone who will govern and will be part of developing something in this province that will give a new definition to what a politician is all about.

I desire to cross all political lines.”

- Lynda Haverstock, April 4, 1989 Saskatoon Star Phoenix

Unfortunately for Lynda and despite the fact she would secure a quarter of the provincial vote in her first election as Liberal leader, political success was not in her cards. In fact, some of what lied ahead for her after winning the Liberal leadership was personally traumatic, terribly unfair and would change both her life and the face of Saskatchewan politics forever.

In 2001, in a piece she wrote for Howard Leeson’s first Saskatchewan Politics anthology, Haverstock described the Liberal Party she’d led til 1995 as in “a perpetual state of self-annihilation”.

Regardless, while Haverstock faced challenges and setbacks during her political career, including electoral defeats and internal party dynamics, her perseverance and dedication to public service left an indelible mark on Saskatchewan’s political history.

As the first woman to lead a major political party in the province, 40-years-old and a single mom, Haverstock broke barriers and inspired a new wave of support for Saskatchewan Liberals.

It wasn’t easy, to be clear.

“Former leaders, some of whom had been considerably younger than (I), had never been described physically in newspaper articles nor was it implied that they were “too young” for the job,” Haverstock wrote in 2001, of her experience as Liberal Party leader.

Eventually, she came to view the media and her political colleagues making incessant references to her age and appearance for what it was: paternalistic and gender discriminatory.

As soon as she was installed as the party’s leader, Haverstock says the same Liberals who talked her into taking the job went “missing in action”. Promises made regarding her salary were abandoned, forcing her to remortgage her personal residence in order to just get by.

Yet under her leadership, the Liberal Party saw increased membership, improved organization, and a reinvigorated presence in the Saskatchewan political arena.

That’s likely why, in a pattern that still holds today, the PC Party would go on to launch vicious personal attacks on Haverstock, including a five-page circular that thoroughly, misogynistically degraded her profession, her politics and her personal life.

We’ll look more at that horrific document - and who wrote it - when we hit 1991.

Lynda Haverstock’s leadership, policies, and personal attributes helped to shape the political landscape of the province, and her legacy continues to resonate with those who value inclusivity, progressivism, and a commitment to democratic principles.

Haverstock's ability to engage with voters, communicate effectively, and build strategic alliances within the Liberal Party of Saskatchewan helped to strengthen its credibility… something MLA Bill Boyd and his PC Party would soon one day need for themselves, desperately.

The Saskatchewan NDP’s leader, Roy Romanow, was installed by the party in 1987 to replace Alan Blakeney.

The Saskatchewan NDP, under the leadership of Premier Allan Blakeney, had championed social justice policies, advocating for accessible healthcare and education and the preservation of crown corporations. However the party had also faced challenges, such as economic recession and public opposition to its left-leaning policies, which had led to decline in public support and internal conflict in Blakeney’s party.

1987 was the second time Romanow, who had been first elected as the NDP MLA for Saskatoon Riversdale in 1967, had contested the NDP leadership. He was an ambitious 30-year-old when he ran the first time (and almost won) in 1970 to replace Woodrow Wilson, then held a relatively high profile in Saskatchewan as deputy premier for over a decade. Romanow played a significant role in the patriation of the Canadian constitution and the creation of Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

The evolution of broadcast communications and print media in the Eighties increased our exposure, even way up in Saskatchewan, to television, movies and music. Celebrities and public figures grew more glamorous and more outrageous, yet also more mainstream.

Subscribed

By the time he was installed as Saskatchewan’s NDP leader in 1987, Roy Romanow was a sophisticated, polished and distinguished 48-year-old politician. A ruggedly handsome son of Slavic immigrants, Romanow was referred to in certain Baba’s circles as a “Ukrainian Robert Redford”.

In true Dipper fashion, a faction of the party was unimpressed.

As Janice MacKinnon wrote in her 2003 book, Minding the Public Purse, after Romanow was elected, one of his problems was, well, his own party.

“…many New Democrats harboured suspicions that Romanow himself was a closet Liberal. Never known as a party man or a union guy, Romanow dressed well and spoke moderately — further causes for suspicion by some on the left.” - Janice MacKinnon, Minding the Public Purse (2003)

He did know how to dress well.

In a piece he wrote for the University of Regina’s Crowding the Centre (Leeson, 2008), Romanow explained how, as Opposition leader in the late Eighties, he fully grasped the rapidly increasing power of personal image and the media, when appointing members of his caucus to their critic portfolios.

“I was looking for men and women who could credibly stand up in the House, pose the questions or make the appropriate statements… I was also looking for them to be able to communicate our core messages to the journalists…” - former Saskatchewan Premier Roy Romanow, Crowding the Centre (Leeson, 2008)

“The decade of the 1980s had been a frustrating one for New Democrats,” wrote Howard Leeson in his 2001 book, in an introductory essay entitled The Rich Soil of Saskatchewan Politics.

“Feeling cheated out of victory in 1986…they could only sit by helplessly and watch as the Conservatives attempted to dismantle much of what the CCF/NDP had put in place over the previous four decades. But with the election of Romanow as leader, optimism began to return to the party.”

With everything he’d already accomplished in his back pocket, at the end of the 1980s, Roy Romanow’s greatest challenge and the defining moments of his career still lied ahead.

Grant Devine deserved to win the 1986 provincial election about as much as Ben Johnson deserved to win the gold medal in 1988.

However, Devine’s folksy charm, political promises and outright rural Saskatchewan vote-buying with taxpayers’ money also proved a powerful drug. All played a role in securing him a second term as Premier.

“You love the sinner but you hate the sin,” then-premier Grant Devine told reporters in March of 1988, after NDP MP Svend Robinson’s historical admission that he was a gay Canadian parliamentarian.

“I feel the same about bank robbers…”

As one of Brad Wall’s final acts of political patronage, Grant Devine sits on the University of Saskatchewan board of governors today. Devine has never been asked to reconcile his very public, very bigoted statements on homosexuality.

I have questions about USask’s participation in Pride Month festivities in 2024, while remaining silent regarding this incredibly shameful historical episode within their own leadership.

But I digress.

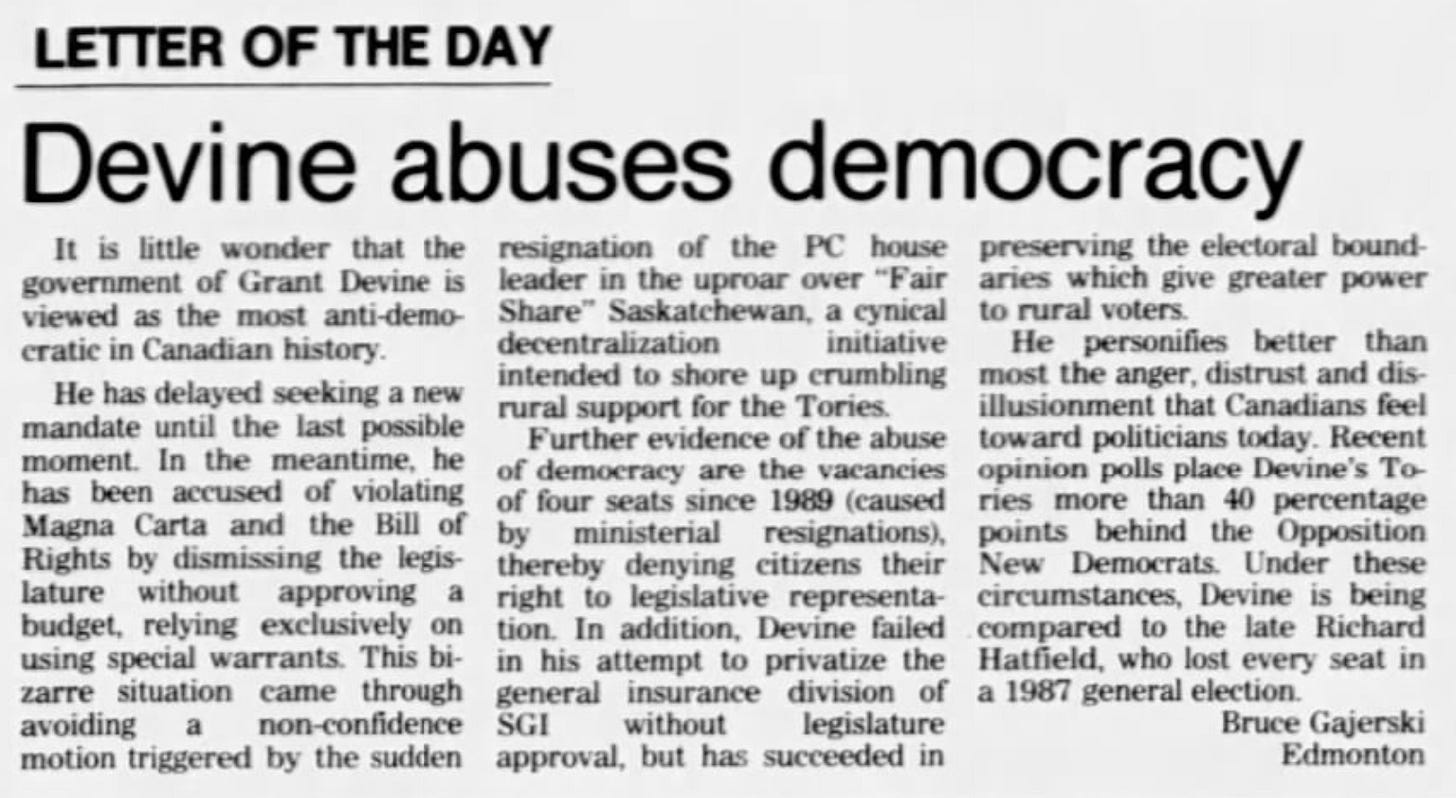

With the Nineties on the horizon, an overconfident and seemingly manic Grant Devine was in his second and clearly final term as premier.

By 1989, Devine’s appetite for running up reckless public tabs had become insatiable.

Accountability for his behaviour and that of his caucus was non-existent.

“…the significant hallmark of the Progressive Conservative government lay in its belief that simply because it held a majority of the seats in the Legislative Assembly it could do whatever it wanted. (Devine’s) government demonstrated this attitude in its cavalier approach to the legislature and to formal demands for executive accountability.”

- Merrilee Rasmussen, The Role of the Legislature, Saskatchewan Politics Into the 21st Century (Leeson 2001)

After carving up and selling off a number of valuable Saskatchewan crown assets, a tipping point had been reached when Devine and his party tried to do the same with SaskEnergy in 1989.

With a fired-up Opposition leader Roy Romanow at the helm, the NDP caucus refused to enter the Assembly when the bell rang, at which they were to debate the SaskEnergy sale bill. A Legislative walk-out by the Opposition ensued, earning overwhelming support from the Saskatchewan public, despite Devine’s frantic efforts to frame the NDP’s actions as an affront to democracy.

The NDP’s rebellion, which lasted for weeks, was bolstered by a public petition that circulated the province with over 100,000 signatures, demanding Devine kill the sale.

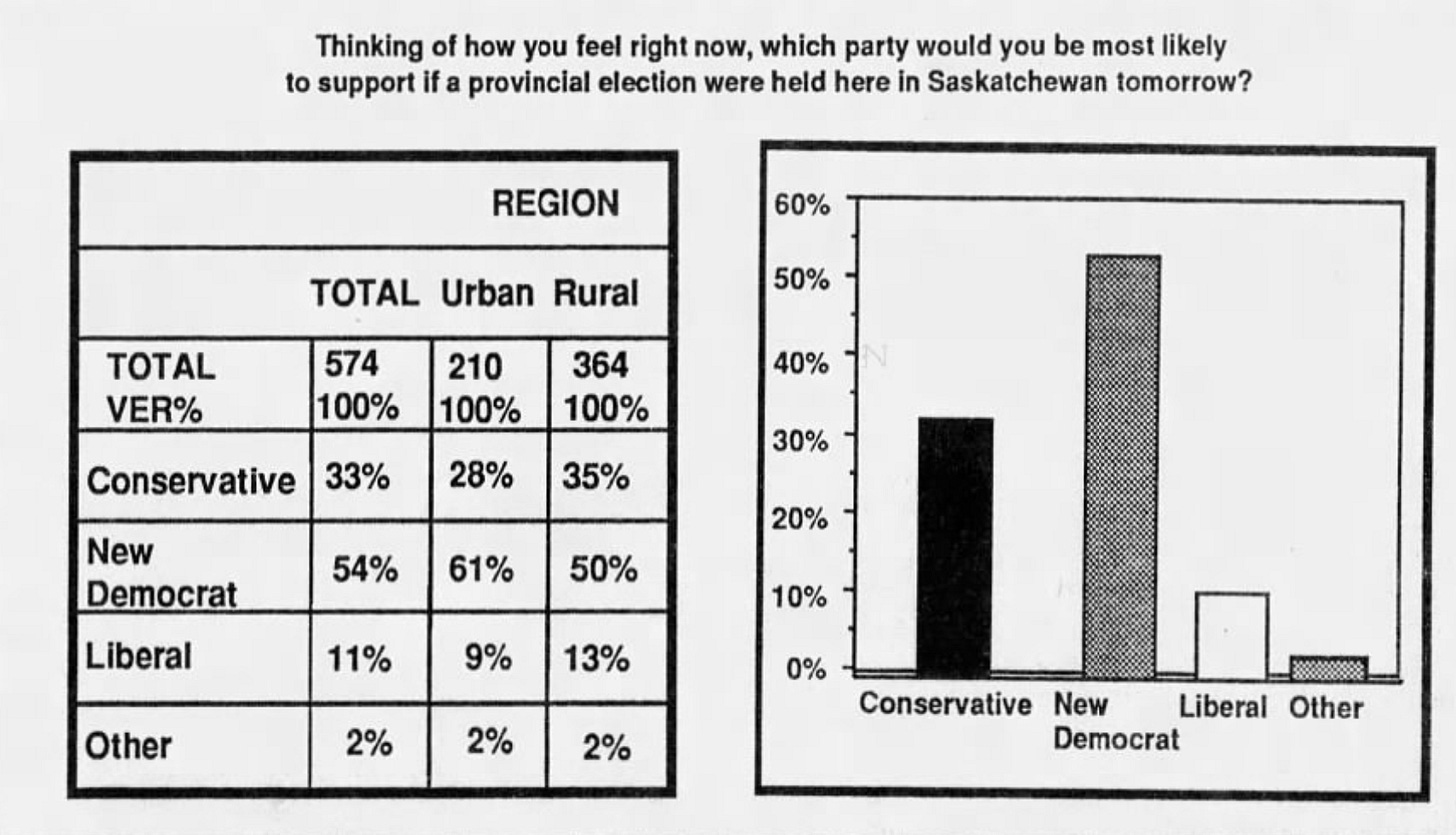

Perhaps the most significant damage to Devine’s plan for SaskEnergy was done by devastating public poll results on the issue, which were published in the Saskatoon Star Phoenix and Regina Leader Post in May of 1989.

A short time later, Devine was forced to pull the sale off the table. The sting of the reality that had been revealed by those polling results, however, lingered.

As the Eighties wrapped in Saskatchewan, Grant Devine knew that as the province’s premier, his time was up.

That he no longer held the support of anything resembling a majority of Saskatchewan people.

Yet Grant Devine chose to stay in the premier’s office until 1991. Under his leadership, the province’s finances were wilfully mismanaged and almost completely bankrupt.

Rather than addressing mounting deficits or making difficult fiscal choices, Devine drained public coffers, perpetrating a vicious cycle of spending and borrowing. Reactionary, expensive patchwork policies helped his government cling to power in the short term, but accelerated Saskatchewan’s inevitable descent into long term economic ruin.

Meanwhile, his caucus was stealing staggering amounts of taxpayers’ dollars, right from under his nose.

As the PC Party government’s second term took off, public money was flying out the Legislature’s front door into rural Saskatchewan and out the back door via the briefcases of Devine’s caucus members.

One MLA would later testify at her trial that she stole $5000 to take a trip to Hawaii out of spite, because Devine dropped her from cabinet.

In the Eighties, MTV was in its infancy, but would become one of the primary drivers of Westernized culture. At the same time, the concept of reality was still largely grounded in physical presence — a state of being, not an entertainment genre.

Defined by bad hair, worse fashion and cell phones the size of a loaf of bread, the Eighties in Saskatchewan, like everywhere else in North America, was a big, brash and bizarre decade. It was a time that highlighted, with brutal precision and clarity, the ideological differences between Saskatchewan's political parties and by extension, its people.

The NDP spent the decade emphasizing social justice and welfare, the PC Party prioritizing economic growth and social conservatism, while the Liberal Party claimed to offer alternative perspectives to both.

As it wrapped, Saskatchewan men who are still today, incomprehensibly, controlling the Sask Party, were just little boys getting their feet wet as staffers in Devine’s Legislature.

Many would go on to dedicate their careers to manipulating and personally profiting off the province of Saskatchewan and the people who built it.

Turns out, it only takes a handful of greedy, petty backroom operatives to obliterate the proud, multi-generational history of pioneering a western province.

We’ll be talking about them too.

In Part 1 of this Prelude, we’ve scanned the political environment of the 1980s in Saskatchewan.

In Part 2, the final part before we crossover into the Nineties, we’ll look at the people and culture of Saskatchewan during the Eighties, including what drove voters (and which voters) to re-elect a flailing Grant Devine.

Prelude to a Grift: The Eighties (Part 2)

The first single from his iconic 1989 album Storm Front, Billy Joel’s We Didn’t Start the Fire was a poignant chronology of what Joel, who had just turned 40, considered to be the decline of American culture since the year he was born.

In his review of the album, John McAlley at Rolling Stone wrote, “As the song rushes toward the present, it catalogs the crises that have compromised our dreams.” McAlley also noted that We Didn’t Start the Fire ends in 1989, “with a spirit-crushing litany of contemporary social horrors.”

The “spirit-crushing social horrors” of 1989 seem positively quaint by today’s standards.

The Eighties were frustrating for New Democrats. The party felt cheated out of the 1986 election by a populist Grant Devine, who false-promised his way to a second term, buying Saskatchewan voters with their own money. However, new leadership, to which Roy Romanow was acclaimed in 1987, combined with the brutality of Devine’s second term, brought with it a new sense of optimism for the Saskatchewan NDP.

Once again the next election, to be held in 1991, held promise of NDP victory.

In 1989, George W Bush Sr had just taken the conservative presidential reigns from Ronald Reagan, but the impact of neo-liberalism, promoted by Reagan and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, had been significant and far-reaching. Reaganomics in the United States led to tax cuts, reduced welfare spending, and increased military budgets. Similarly, Thatcher's economic policies in Britain aimed to reduce the power of unions and boost industry competitiveness through privatization.

Critics still argue passionately over the fiscal policies of Reagan and Thatcher, with many claiming they exacerbated income inequality, weakened social safety nets and contributed to multiple financial crises.

Grant Devine found both world leaders inspiring, mirroring their policies and attitudes.

Reagan, Thatcher and even Grant Devine, in conjunction with their fiscal policies, proved a stark political contrast to the disintegration of communist strongholds that dominated global affairs during their tenures, particularly after the emergence of the OPEC cartel.

Back in Saskatchewan the mood was light, despite the fact the province’s finances were (somewhat secretly) in a death spiral.

Regina mayor Doug Archer presided over a jubilant Queen City, still riding the high on the Saskatchewan Roughrider’s 1989 Grey Cup win.

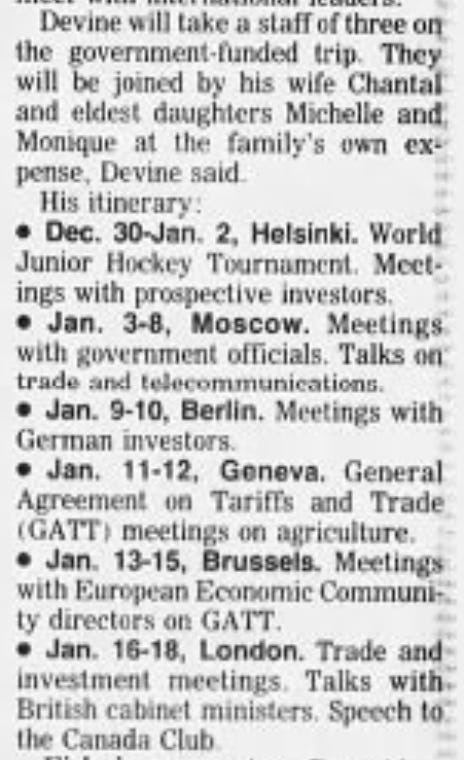

Meanwhile, premier Grant Devine and his family were getting ready for the publicly-funded trip of a lifetime.

Why did the Saskatchewan taxpayer need to finance Grant Devine’s travel to the World Juniors in Finland?

Who cared?

Not Grant Devine.

Because as the thin winter’s light dimmed over a frigid, frustrated Saskatchewan in late 1989, it was clear the people of the province no longer trusted or wanted him as premier. In turn, Grant Devine would go on to show Saskatchewan people how much he didn’t want or need their permission to run this province into the ground.

As you read in the previous chapter, in 1989 Devine and his corrupt caucus had just been shocked by a provincial poll, conducted by and published in the Star Phoenix and Leader Post. The results were decisively, overwhelmingly anti-Devine and anti-PC Party. As was common at the time, broadcast media outlets followed the newspapers’ poll results with their own extensive coverage, meaning anti-Devine sentiment was everywhere.

The cornerstone of Devine’s privatization agenda, the fire sale of SaskEnergy, had just been thwarted by the Saskatchewan NDP and their ongoing protest strike of the Legislature. However, the sale’s death blow was dealt by the same newspaper poll that exposed Devine’s plummeting popularity. It also revealed Saskatchewan people unequivocally wanted to keep the Crown.

So Grant Devine might not have been feeling warm and fuzzy about Saskatchewan, as the plane whisked his family up and away, bound for the Soviet Bloc.

What did Grant ‘Give 'er Snoose’ Devine have to offer the Kremlin in the midst of the Soviet collapse?

Who cared? Not Grant Devine.

In 2024, the most interesting thing about Devine’s 1989 publicly-funded Moscow trip was the number of Saskatchewan journalists who went with him. While they traveled on Devine’s itinerary, their travel expenses were reimbursed by the media outlet.

That practise died long ago in Saskatchewan. The Sask Party has systematically dismantled the mechanisms we once used to hold the government accountable, including how it interacted with media. The second reason was cash-strapped, budget-slashed newsrooms ran out of money to pay for it.

In the Eighties and Nineties, Saskatchewan voters wanted, expected and received far more information, from both the media and provincial government, than they get today.

Even after reluctantly agreeing to reduce it from nine to seven percent, as the Nineties loomed, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney could not appease Canadians outraged over his incoming Goods & Services Tax (GST).

John Turner was in his final days as leader of the federal Liberal party. Audrey McLaughlin had just replaced Ed Broadbent as leader of the federal NDP. Broadbent would go on to be appointed, by Mulroney, as the president of the International Centre for Human Rights and Democratic Development.

Back then, federal leaders weren’t petty bitches.

Not all the time, anyway.

Mulroney was less likely to show diplomacy on the construction of the Rafferty-Alameda dam.

In February 1986, Premier Grant Devine met with American politicians, formally kicking off the project, managed jointly between Canada and the US. The dam was North Dakota’s idea, blaming Canada for flooding woes in the state. The benefit to the province, claimed the provincial government, was the dam would provide water for irrigation (in certain ridings, coincidentally, big supporters of Devine’s party) and as coolant for Sask Power’s new Shand power plant.

Not that Devine had to be convinced. Rumors of the project caused land prices in the riding of PC Party MLA, senior cabinet minister and bargain bin-Dick Cheney, Eric Berntson, to skyrocket.

They also caused outrage.

Publicly, the details were murky. Pundits, the Saskatchewan NDP Opposition and newspaper editorials demanded more information; a cost/benefit analysis, for example. Devine would only state, vaguely, that taxpayers would be out between $100 and $200-million on the dam’s construction.

That’s a huge, reckless unknown gap; in today’s dollars, between a quarter and a half-billion.

Ranchers who grazed cattle upstream from the Rafferty-Alameda site were furious at the prospect of losing land, accusing the premier of putting his relationship with America before Saskatchewan people. Environmentalists lost their minds over the potential loss of thousands of acres of wetlands and the annihilation of fragile prairie ecosystems.

A string of legal and political challenges, launched by those groups and others, plagued Devine’s PC Party government and the dam project throughout its construction.

Devine forged ahead regardless.

“In government, you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t, so we’re going to dam it anyway,” boasted Devine, evoking one of his beloved, folksy tropes, in a speech he cheerfully delivered as controversy over the project raged.

The federal license for the Rafferty-Alameda project was issued by the Mulroney government in June 1988, not that its absence had been holding anything up. The Devine government had commenced construction of the dam months earlier without one, on a wink and a nod from Mulroney that there would be no consequences.

September 1988: a fiesty, fresh-faced staffer from the federal Ministry of Environment burst into the news, alleging the Rafferty-Alameda licensing process was a farce.

A senior policy advisor to Mulroney’s federal Minister of Environment, Elizabeth May, 34, charged that backroom conservative operatives from Ottawa and Saskatchewan struck a deal to circumvent Canadian law. She alleged that instead of environmental protocols and assessments pre-empting the license, political favours had been exchanged between Devine and Mulroney.

May’s disclosure prompted the United States government to pause funding their side, at least until environmental issues were sorted out. A month later, November 1988, the Canadian Wildlife Foundation (CWF) launched its lawsuit against the project, adding to a growing list.

May resigned from Mulroney’s government. A year later she helped launch the Sierra Club.

In the spring of 1989, a Canadian federal court justice revoked the license for the construction of the Rafferty-Alameda dam, over environmental infractions. In the fall, the Mulroney government reinstated it. What ensued was a dog’s breakfast of jurisdictional bureaucracy, overreach and outright law-breaking.

In all this, a historical development. As the Eighties were slinking off the stage, Canadian courts recognized, for the first time and in a ruling against Saskatchewan, that federal environmental guidelines were legally binding.

As part of that ruling, three days before New Year’s, a judge ordered more environmental-protocols for the dam. Construction would need to be paused, again. After months of wild instability, the judgment left workers to face the New Year and the Nineties with their income, just like the dam’s future, up in the air.

They’d be comforted soon enough, because Grant Devine, as he faced an existential threat to his tenure in the premier’s office, would bulldoze anything, including federal laws.

25 years after Rafferty-Alameda was built, in 2011, North Dakota would experience one of the worst floods in its state history.

On December 6, 1989, a misogynist walked into Montreal's École Polytechnique and fatally shot 14 young women, just because they were women. Technically this was one of the world’s first school shootings, before the term “school shooting” became part of the lexicon of daily life. A few years later, Columbine would sew up that dubious distinction.

Brutal violence was rocking countries involved in regional conflicts across the world, from Romania to Panama. Nelson Mandela was still in prison, on the verge of release.

Meanwhile, as he was actively destroying hundreds of acres of farmland by Estevan, Grant Devine was threatening the country that “time was running out” for Saskatchewan’s ag industry. Poor to fair crops had brought in low prices that year. Yet, despite Devine’s demand for $500-million from the feds, Mulroney said prices weren’t low enough to send a stabilization payment.

Saskatoon, under relative newcomer mayor Henry Dayday, had the second highest unemployment rate in Canada at 10 per cent. Molson’s Brewery, a critical local job creator, was about to be sold to a group of its employees.

On December 30, 1989, this blurb ran on the cover of the Star Phoenix’s free, home-delivered spinoff product, the Prism.

Spoiler alert: it wasn’t.

As the faint new light of the Nineties dawned, Saskatchewan moviegoers, including those in the many rural cities and towns that still had a functioning theatre, were blessed with quality and choice (though this may not have been as apparent at the time). Cinematic offerings of the day included Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing; Drugstore Cowboy; My Left Foot; Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade marked the third installment in the franchise; Batman; When Harry Met Sally; Driving Miss Daisy; Born on the Fourth of July; Steel Magnolias; sex, lies and videotape and The Fabulous Baker Boys.

Perhaps Dick Spencer, a longtime conservative architect, former campaign strategist for John Diefenbaker, mayor of Prince Albert and apologist for Grant Devine, best summed up the mood as Saskatchewan entered the Nineties and the final years of Devine’s last term:

“(Devine and his MLAs) knew the economy, much of it was beyond their control, was in shambles, and that many of their high-priced promises could not be kept. They knew their deception about the 1986 budget deficit would be exposed and the provincial debt would continue to climb dangerously… They knew they were now being scrutinized by a wary public and a cranky media. They knew the business community was uneasy, the labour leadership hostile and the provincial civil service disoriented.

Yet, in desperation, perhaps in colossal näiveté, they pushed on to rescue the economy and themselves with neo-conservative schemes of privatization and experiments in decentralization that would not work.” - Dick Spencer, Singing the Blues: The Conservatives in Saskatchewan (U of Regina, 2007).

If that’s what Devine’s friends had to say about the end of the Eighties, it’s safe to say the reality was worse.

Let’s also not forget that while Devine’s caucus was pushing to “rescue… themselves with neo-conservative schemes”, many of the MLAs in it were wilfully, deliberately and criminally stealing from Saskatchewan people and their government.

With that, we leave the Eighties to march into the Nineties, a decade that is typically pulled apart, dissected and reassembled in the image of whoever you’re talking to at the moment.

For some, the Nineties marked a time where leaders put province before party and made difficult but necessary decisions. Others feel the Nineties was the decade that killed what Saskatchewan could have been, devastating rural communities with healthcare and education cuts that were rooted in partisanship, not fiscal necessity.

What’s undeniable is the Nineties were pivotal in creating the Saskatchewan that has unfolded around us today. Understanding how previous Saskatchewan leaders and voters navigated crises or implemented successful reforms can inspire us to emulate their successes or learn from their failures. In essence, examining the facts about Saskatchewan’s political past not only helps us gain a deeper appreciation of where we come from, but also serves as a roadmap for charting a more informed and sustainable course towards a brighter future.

Consider this book akin to going through old photos from that questionable phase in high school — sure, it may be cringe-worthy, but it also helps us see how far we've come and what we don't want to do over.

See you in 1990, or Chapter 1.

Chapter 1: January - June 1990

It was a classic January in Saskatchewan.

As the province slowly clambered back to life, headed back to school or the office after the Christmas holidays, its residents were sluggish from overeating, frozen temperatures and the grim realization that winter was not yet half over.

For workers earning a living building southern Saskatchewan’s Rafferty-Alameda Dam, the New Year and the new decade opened on a disconcerting note. In late December a Canadian court judge demanded an environmental assessment on the project, a requirement of federal law willfully bypassed by both Devine and Mulroney governments. The judgment meant dam-related jobs and livelihoods were at risk of being shutdown, for a second time.

In his book Dams of Contention, Bill Redekop describes the Rafferty-Alameda Dam project as “a snapshot of the birth of environmental law in a society that wasn’t entirely ready for it. American environmental law was a generation ahead of Canada’s at the time. That’s why North Dakota looked to Saskatchewan to get the dams built.”

The Legislative Assembly wouldn’t reconvene for another three months. Premier Grant Devine was out of the country, schmoozing the collapsing Soviet Union for business opportunities. He and his family would return home on the same day an attack by Azerbaijani militants resulted in fierce ethnic fighting and blood running in Moscow streets.

Back in the province, Devine quickly learned the situation wasn’t ideal either.

A new decade meant new spin.

Speaking to reporters after his Eastern European jaunt, Devine foreshadowed a deficit budget - his eighth in a row. He also insisted he would only raise taxes on sinful things like cigarettes and alcohol, providing cold comfort for an anxiety-ridden, destitute population, reliant on its few vices.

Meanwhile, the Conference Board of Canada breathlessly announced that the Saskatchewan economy would lead Canada’s in 1990… if the weather and grain prices held.

A big If.

Because everything old is new again,

in January of 1990 this message was sent by SaskPower to the federal government:

Yes almost 35 years ago the Devine government, ran by the same people who run the Sask Party’s, moaned to Brian Mulroney’s federal government that SaskPower would be destroyed by any national action to mitigate climate change, especially reducing coal-fired electricity.

Today, the province of Alberta has weaned itself off coal entirely, thanks to a plan that was designed and implemented by its government in under ten years.

Rumors of labour discontent in Saskatchewan’s public education system became reality in early 1990, when Regina teachers threatened a half-day walkout to protest lack of progress on their contract. Intermittent job action continued in both Regina and Saskatoon throughout the remainder of the school year.

In February, Nelson Mandela’s imprisonment ended and hope raged eternal that he could further close South Africa’s brutal racial divide and end its white minority government.

Meanwhile, the City of Saskatoon had still not sworn in its first female police officer.

In March of 1990 the RCMP ruled that orthodox Sikh members could wear a turban with their uniform. The decision followed months of lobbying against it by Western Canadian special interest groups, including a petition that was backed by some Conservative MPs.

It would be a historical moment in Saskatchewan as well.

SARM, which was in the midst of its annual convention when news of the RCMP’s decision broke, put forward a resolution on the matter. SARM delegates voted 1000-1 in favour of RCMP officers only wearing stetsons.

The lone voice of dissent was an Aberdeen-area farmer named Ron Peters.

“Equality is not sameness. The RCMP have respect worldwide for the quality of their work, not for their uniform.”

Peters, in an impassioned speech from the podium before SARM members cast their ballot, implored his peers to consider the implications of their vote. He was the only person in the room who came down on the right side of history, leaving 1000 members of virtually every rural municipality in Saskatchewan represented by these words:

“If they want to wear turbans, they should go back to their own country…If they live here they should do as Canadians do.” - Gord Chaban, SARM delegate for Saskatoon, to reporters in March 1990.

Maybe Carl from Odessa (pop. 201) did a better job summarizing the sentiment:

“It’s played an important part in our history. My niece and nephew are in the RCMP and it’s a tough life. Respect that.” - Carl Hoffman, Saskatoon Star Phoenix, March 16, 1990.

What do Carl’s niece and nephew have to do with whether Sikh RCMP members should be allowed to wear turbans? Only Carl knows, who hopefully was not an accurate representation of the overall level of intelligence held by attendees of the SARM Convention of 1990.

Imagine being the single voice of dissent in a room of one thousand other people, finding yourself unable to bring even one around to your perspective. Peters was well-known in his community for being an outstanding person of good character, but according to his family, it still hit him hard.

Tthe vote was one thousand to one that day… and the one was right. A powerful reminder of what change in Saskatchewan has always looked and felt like: insurmountable.

Delegates who attended that convention were not only from across the province, but from across all political stripes. In the Nineties, racism and bigotry were not divided by party lines.

It seems prudent that SARM might consider posthumously recognizing the extraordinary example of Ron Peters.

PC Party caucus communications director John Scraba used the regimented media schedule he’d created for Budget Day, March 29, 1990, as cover to slip out of the Saskatchewan Legislature unnoticed.

That morning journalists and the NDP Opposition caucus were tucked away in their offices in “lockup”, a process that involved pouring through embargoed, confidential, advanced copies of the 1990 Saskatchewan budget.

It is still standard practise today. The extra lead time ensures journalists have their stories and responses ready in time for dinnertime news casts and print news deadlines. It also gives the Opposition a reasonable window of time to be able to prepare a timely response.

Lockup is one of the few, if not unfortunately-named, professional courtesies still enjoyed today between the Government of Saskatchewan, its Official Opposition and local media.

So knowing that the chance of being spotted was less than normal, Scraba schlepped through downtown Regina’s snow and dirt encrusted streets, a briefcase full of stolen public money clutched in his gloved hand. He was headed for the Cornwall Centre’s branch of the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce (CIBC).

After stomping the snow off his boots, Scraba told the bank teller he wanted to open a safety deposit box. He used the name “Fred Peters”. Peters was Scraba’s colleague in the Legislature, an assistant to Finance Minister Lorne Hepworth. The address Scraba provided to rent the box was Room 201 in the Saskatchewan Legislature, the PC Party caucus office, where (the real) Peters and Hepburn had been preparing for Budget Day events since the wee morning hours.

There was so much stolen cash lying around his office that Scraba went back to the Cornwall Centre, on that same morning, to stuff a second briefcase-full into the safety deposit box. Scraba would later testify he felt relieved that a dirty job was done.

The pilfered public money was out of his desk and safely tucked away.

Visibly relaxed, Scraba grabbed his tape recorder and walked back out into the cavernous hallways of the Saskatchewan Legislature. Moments later, he would face a wall of reporters, ready to spin the province’s finances.

That afternoon the PC Party’s 1990-91 budget delivery was lacklustre, dragged down even further by a projected $363-million deficit. Dubious government accounting rules of the day masked a much more troubling financial picture for the province, but it would be a while yet before that information would fully come to light.

In 1990, Saskatchewan farmers had high hopes that Devine would come through with spring seeding subsidies. Instead, the provincial budget included a new loan program, repayable at 10.75% interest. That rate was still better than what was available through traditional lenders, given the Bank of Canada’s (BoC) prime rate was over 14% at the time.

A week after releasing that unpopular budget in 1990, Devine turned on his ally, Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. In a scrum with reporters in Regina, the premier spat angry separatist tropes and blamed the federal government for everything that had ever outraged Saskatchewan farmers.

“There’s a lot of discussion these days about a distinct society. You’re looking at an extinct society in Western Canada.” - Premier Grant Devine, May 3, 1990 Regina Leader Post

A few days later, Devine had a meltdown in a room full of agriculture stakeholders who had rejected his 10.75% loan proposition. It had been a relatively cordial meeting, until Devine learned the next one would be held in a union hall. Despite the organizers’ insistence that using that hall was a matter of convenience, Devine was outraged, convinced it was part of a broader plot against him.

Hollering “You’ve played your hand!” and “If you’re serious you won’t play politics!” at shocked attendees, Devine stormed out of the meeting.

On Budget Day, John Scraba spun the cost of the 10.75% loan program as $40-million. He was lying. Had the BoC prime rate held, that price would have been exponentially higher. Instead, the rate peaked in spring 1990 at 14.75% and began to drop.

The taxpayer didn’t lose its shirt after all.

It was a rare occurrence.

Lorne McLaren should have been a big deal.

A popular local businessman from Yorkton, McLaren swept his riding for the PC Party in 1982. Prior to that Yorkton, affectionately tucked away behind Saskatchewan’s “Garlic Curtain”, had been staunch NDP territory.

After McLaren nailed that win for Devine, his reward was a position in the premier’s first cabinet, as well as responsibility for two of the Crown jewels of the province’s publicly-owned portfolio: Potash Corporation of Saskatchewan (PCS) and SaskPower. The added duties meant more power, responsibility and a significant pay hike over his $53,000 MLA salary.

Yet as the first half of 1990 drew to a close, Saskatchewan print journalist Dale Eisler wondered why McLaren had been demoted to Grant Devine’s back bench, then more or less disappeared from public view.

In a June 28, 1990 column that ran in the Saskatoon Star Phoenix and Regina Leader Post, Eisler outlined McLaren’s personal financial woes, then linked them to the mild assertion that McLaren had been demoted due to a conflict of interest that wasn’t being shared with the public.

After painting that picture for his audience, Eisler reiterated that his theory was conjecture… probably.

Plausible deniability was one of Grant Devine’s saving graces, but Eisler’s theory wasn’t wrong. In fact, the truth of the matter wasn’t just “compromising”, it was criminal.

The real reason McLaren had lowered his public profile and opted to lurk behind the scenes would have blown Dale Eisler’s mind. A few years later, it would land McLaren in jail.

Spring in Saskatchewan came and went in the blink of an eye, completing the transformation from frozen hinterland to summer prairie virtually overnight.

A classic tradition.

News on the Meech Lake Accord - a series of proposed amendments to the Canadian Constitution, which the province of Quebec had refused to sign in 1982 - was everywhere.

The Meech Lake Accord was all about amending the constitution to recognize Quebec as a "distinct society" within Canada. It also weakened federalism, granted provinces greater powers over immigration and offered a constitutional veto to provinces over future amendments.

The accord required ratification by all ten provinces within three years of its inception. This created a June 23, 1990 deadline, which coincided with the federal Liberal party’s leadership convention.

A bitter rivalry between candidates Paul Martin and Jean Chrétien had divided its membership, largely down pro and anti-accord lines. Martin was onside with Meech Lake unequivocally. Jean Chrétien’s support was tepid at best, earning him the ire of his home province of Quebec.

On a warm Calgary weekend, the first of summer 1990, Martin was knocked out in the first round after Chrétien secured over 50 percent of the vote. At that, the Liberal Party convention, held under the distinctive roof of Calgary’s Olympic Saddledome, exploded into both cheers and jeers.

Saskatchewan’s Liberal Party leader Lynda Haverstock was appalled when a cluster of young Quebecois members loudly booed Chrétien’s acceptance speech. Confidently and assertively Haverstock, who had not pledged allegiance to either federal leadership candidate, marched over and asked the disgruntled French youth to instead project unity for the sake of the greater good.

Speaking to reporters after his win, Chrétien referred to Haverstock as a “very attractive lady” and promised to support her efforts to elect more Liberals to Saskatchewan’s Legislature.

Thousands of miles to the east, a pale, shook Brian Mulroney tried to put a positive spin on a massive personal and political failure.

It had been so close. Just a few weeks earlier, all ten Canadian premiers had promised to sign off on the accord before its deadline. Then Manitoba and Newfoundland backed out at the eleventh hour, leaving the deal to die on the table as its midnight deadline came and went.

After the deal collapsed, Quebecers burned Canadian flags, booed the anthem and swore to exit Canada. From there the hurricane force of separatist sentiment in Quebec only kept gaining momentum.

In 1990 Grant Devine was the only premier in Canada who didn’t make a statement on the day the Meech Lake Accord died. Perhaps with the weight of his disastrous latest provincial budget on his mind, Devine said he wanted to talk to Mulroney first.

Briefly, let’s now rewind this tape even further, back to a crisp early October morning in 1986.

At 7:30AM Eastern the sun was rising over Ottawa’s Parliament Hill, already up for hours, thrumming with the business of running the country.

It was still dark at 5:30AM in Saskatchewan, where a panicked Grant Devine sat awake in his room at the Sportsman Motel in the town of Kelvington (pop. 900). Whether it was the beginning or the end of a long day is unknown, but he was definitely stressed out.

It had been just over a week into what was shaping up to be a grueling provincial election campaign. Despite the fact CBC had just released poll results suggesting a win was well within his grasp, Devine was not convinced.

Each room in the Sportsman Motel boasted a bedside rotary telephone, perched on a nightstand screwed into the wall. That’s how Devine ended up unwittingly screaming through the motel’s paper thin wall, directly into the ear of the newspaper reporter asleep in the room next door.

“IF I LOSE THIS IT’S GOING TO BE DAMN TOUGH FOR MULRONEY NEXT TIME AROUND!”

Devine shouted into the receiver, likely at Doug Wise, Mulroney’s federal Minister of Agriculture.

Jolted awake from a dead sleep, the reporter, who had been assigned to follow Grant Devine on the campaign trail, fumbled for a pen. Mulroney must announce at least a billion dollars in aid for farmers or, Devine shrieked, the federal Tories would lose a loyal conservative government ally in Saskatchewan.

A few hours later, rising in the House of Commons, an increasingly unpopular Brian Mulroney would announce one billion dollars in aid for western Canadian agricultural producers.

“Grant Devine had asked his Ottawa Tory friends for help,” wrote longtime Saskatchewan conservative operative Dick Spencer in his book Singing the Blues: The Conservatives in Saskatchewan. “Then, in an open-necked plaid shirt and cowboy boots country costume, he stumped the province taking credit for every dollar.

Why not?”

In 1986, Brian Mulroney saved Grant Devine’s political career and handed him a second term with that one-billion dollar promise to farmers.

In 1988, the Supreme Court ruled that Canada’s founding French-language laws still applied in Saskatchewan, so technically any of the province’s laws written solely in English were invalid. It stated that the Saskatchewan government had to rewrite all provincial laws in French, or change provincial law to state English-only laws were valid.

Devine decided to do both.

This would not only appease Mulroney, who desperately needed every Canadian premier onside with his French-English unity push, but it gave Devine’s government the opportunity to make some money for its friends and donors. That is how Saskatchewan was introduced, thanks to Eric Berntson’s backroom machinations, to the money-losing failure that was GigaText.

Grant Devine had agreed to sign the Meech Lake Accord, despite the fact he had no reason to believe it had the support of Saskatchewan residents. He’d also obediently supported Mulroney’s nationally panned proposed GST.

By the midway point of 1990, construction on Rafferty-Alameda dam was back in full swing, because Mulroney’s government was still purposely, studiously ignoring Devine’s deliberate snub of federal court judgments and Canadian environmental law.

Perhaps former Reform MP Elwin Hermanson, who would later go on to lead the Saskatchewan Party, put it best when he rose in the House of Commons in Ottawa in 1995 to speak to that year’s Quebec referendum:

“Premier Devine sat at the table and said: "I will go along with this Meech Lake accord idea, but I want something for it"… he said: "I will sell my soul for a billion dollars.” I spoke shortly after that decision with an aide of one of his MLAs. This was during the time of the GST debate when the federal government was trying to implement the GST. I said to this member's aide: "Why did our provincial government agree to lend support? Why are we going on with the GST and why are we going along with the Meech Lake accord concept?" Very honestly this assistant said: "You have to do something to get a billion dollars." - Reform MP Elwin Hermanson, House of Commons, November 30, 1995

Hermanson refused to provide a name, but a smart gambler would put money on that aide to one of Devine’s MLAs being Brad Wall.

Are you seeing the pattern here yet?

As the smash hit Pretty Woman was wrapping its record-breaking theatrical run, Devine and his government had bucked the time-honored tradition of warring with Ottawa. This was refreshing for some Saskatchewan residents. The premier’s willingness to cooperate with the Prime Minister’s office had undoubtedly yielded rewards, at least for Saskatchewan’s rural voters.

Mel Gibson and Goldie Hawn teased moviegoers with their chemistry in Bird on a Wire, while Driving Miss Daisy had just cleaned up at the Oscars. Gremlins 2 and Back to the Future III were also in theatres, hallmarking the era of the cinematic sequel.

Canadian blind guitarist Jeff Healey was a darling of the North American music scene, to the extent he declared the accolades for his work that poured in from the likes of George Harrison, Eric Clapton and other legends “boring”.

Mulroney was licking his Meech Lake Accord wounds as “Step by Step” by the New Kids on the Block soared to the number one spot on Billboard charts, which they shared with the likes of Roxette, Phil Collins, Wilson Phillips and Bell Biv DeVoe.

New episodes of Cheers, Roseanne, Full House and Murder She Wrote kept Saskatchewan residents glued to their TVs as they hotly anticipated upcoming season premieres of their favorite sitcoms. The Simpsons and Married… With Children were delighting and horrifying curious viewers on FOX.

Brad Wall, John Gormley, Reg Downs, Kevin Doherty and Jason Wall are just a handful of the Saskatchewan men heavily influencing provincial politics today who, as the Nineties dawned over Saskatchewan, were working behind the scenes in the Legislature for Grant Devine.

Chapter 2: July - December 1990

Regina residents Don Castle and Darrell Lowry were just happy to be home.

The president and vice-president of the Saskatchewan Transportation Company (STC) had been stuck in the United States since February of 1990, awaiting trial after being charged under Jimmy Carter’s Foreign Corrupt Practises Act (FCPA).

At the heart of the matter was a contract for fifty new buses from a company called Eagle Bus Manufacturing in Brownsville, Texas. The allegation was that Eagle kicked $50,000, or two percent of the contract value back to Castle and Lowry, who were charged under the pretense that both were representatives of a foreign government and accepted a bribe.

Castle and Lowry faced heavy fines and up to five years in a Texas state prison if found guilty.

In early June 1990 a Dallas judge threw out the charges, stating the FCPA was only applicable to American citizens. That decision was immediately appealed by the FBI, leaving Castle and Lowry in limbo in respect to their release conditions. While initially a judge decided both men had to stay in the United States waiting for a resolution to the FBI’s appeal, their lawyer successfully argued they should be free to travel between the two countries.

Both men were finally allowed to return to Regina, where they were about to face another inquiry into their activity, called for by Grant Devine’s government.

Sandy Monteith had entertained Rider fans at Taylor Field with his pyrotechnical stunts for as long as anyone could remember.

Every time the Riders scored a touchdown Monteith, affectionately known by Regina fans as “The Flame”, would flick a lighter at the container of flammable powder affixed to the top of his head. A strong flame would shoot straight up into the air, the heat from which could be felt by fans several sections over.

In fact, The Flame had been banned from Taylor Field in the late 1980s over safety concerns, but was allowed back after he and then-Saskatchewan Roughriders GM Al Ford came to a “verbal agreement” that Monteith would keep his act in the end zone.

The mood was jubilant on a warm July evening in 1990, as fans tumbled out of Taylor Field, riding high on the last-minute win the Riders had just pulled off against the Hamilton Ti-Cats.

On game days The Flame could always count on Rider fans for a hand hauling his gear in and out of Taylor Field, including a suitcase full of highly-flammable materials. Monteith later admitted he didn’t know a fifteen year old boy was carrying that suitcase, when it exploded in the parking lot that night. The boy endured second degree burns to a quarter of the his body.

A few months later, October 1990, Monteith was fined $200 by a sympathetic judge, for two counts of violating federal explosives’ regulations. That season he returned to Taylor Field to watch the Roughriders, sans any pyrotechnics.

Once again The Flame’s future and legacy was potentially about to go up in smoke.

An Angus Reid poll released mid-July 1990 showed Preston Manning’s federal Reform Party receiving support from four percent of the poll’s decided Saskatchewan respondents.

That four percent was only slightly less than half of the support Grant Devine’s governing PC Party received in the same poll, despite the fact Manning had stated his party would not be participating in the next provincial election in Saskatchewan. The PCP reflected a rock bottom 11 percent of the decided vote; the Saskatchewan NDP 32 percent.

Support for the Liberal Party, led by Lynda Haverstock, stood at 23 percent, while a whopping 33 percent remained undecided.

“My goal is to ensure a minority government; I happen to believe that’s the best form of government” - Lynda Haverstock, Regina Leader-Post July 12, 1990

Knowing Devine was going to be forced to call an election sooner or later, Haverstock was in the midst of what she had dubbed her “listening tour”. The schedule to which Haverstock had committed was grueling, with days or weeks at a time on the road, sometimes living with complete strangers.

That grind, in part, somewhat impeded her efforts to simultaneously build a party with credibility in the Legislature. She was only one woman... and she was a woman, which was an issue from the moment she won.

“At the time, the number of comments and questions from reporters and members about (Haverstock’s) age and appearance did not seem important. Later in her tenure, however, it became an annoyance. Former leaders, some of whom had been considerably younger than she had never been described physically in newspaper articles nor was it implied that they were “too young” for the job.” - Lynda Haverstock, Saskatchewan Politics, Into the 21st Century (Leeson)

Not long into her tenure as Liberal Party leader, Haverstock realized she’d been abandoned by the people who had convinced her to run for it in the first place. She made an effort to reach out for guidance from her predecessor, former Saskatchewan Liberal leader Ralph Goodale, but was rebuffed. Without the support of her party brass, she was forced to make difficult choices.

For example, because the leader’s salary the Liberal Party had promised Haverstock did not materialize and she was committed to growing the party, not her own once-thriving farm counseling service, at this point in time Haverstock was forced to remortgage her home in order to pay herself.

Over the course of the next few years Haverstock would be punished extensively by her opponents and her own supporters in the Saskatchewan old boys club, including in the press gallery, for her optimism, likeability and audacity to challenge their power.

“Less than five weeks after taking over the helm of the Saskatchewan Liberals, the media complained that Haverstock was nowhere to be found… Comparisons were drawn between Haverstock and her predecessor, Ralph Goodale, the latter praised as a permanent “fixture around the legislature in the days before he had a seat.” - Lynda Haverstock, Saskatchewan Politics, Into the 21st Century (Leeson)

In the meantime Haverstock remained undeterred, cheerfully oblivious to just how nasty things were about to get for her.

Hunched over his desk in his office, John Scraba was doing something that had become second nature to the one-time radio disc jockey: forging invoices for Grant Devine’s MLAs. This time the task was being conducted on behalf of Eric Berntson, who had requested a sum of approximately $8000 in advance of his planned departure for the Canadian senate.

Pulling out a clean, blank invoice emblazoned with the fake company details of Airwaves Advertising, one of the shell companies he’d set up to facilitate the fraud, Scraba carefully began filling in the details.

Dating the first invoice June 1, 1990, he entered “Audio presentation: Recording, dubbing, speeches” as a description of services rendered. That invoice total was $4,375.00.

Then Scraba dated a second Airwaves Advertising invoice July 5, 1990, billing the taxpayer $3,495.00 for “Newsletters: Constituents of Souris Cannington Consultation, production, distribution, Session Highlites”.

Both invoices were attached to a Request For Payment (RFP) form, which in mid-July of 1990 was submitted to the Saskatchewan Legislature Department of Finance for payment. Later, at trial, Scraba would indicate that Berntson was adamant he needed the cash quickly that summer.

On August 29, 1990, Scraba heard from the PC Party’s Regina-based law firm, Wellman, Andrews, Blais & Butler; Airwaves Advertising had mail, could Scraba come pick it up?

Knowing payment for Berntson’s phony invoices had arrived from the Saskatchewan Legislature, Scraba picked up the envelopes and rolled into a downtown Regina bank to make a deposit into the Airwaves Advertising account. On the same day he wrote a cheque from Airwaves Advertising to the PC Party and deposited it into its caucus account, from which he withdrew over ten thousand dollars in cash.

Some of that cash went into the CIBC deposit box. The rest was stuffed into an envelope and Scraba called Berntson’s house, letting his wife know the package was ready. Berntson met Scraba at his office in the Legislature, where the envelope changed hands.

Of course, no costs had been incurred by Berntson with respect to any of it, nor did Airwaves Advertising even exist.

On July 19, 1990, MLA Eric Berntson resigned from his role in Grant Devine’s caucus. Two months later he was appointed by Brian Mulroney to the Canadian Senate.

Mulroney was stacking the senate with supporters to ensure his dreaded GST bill would pass into law. This created a new, unwelcome chink in Grant Devine’s political armor, which was crumbling and cracked already by the death throes his government was experiencing. The GST was wildly unpopular and his government was tightly connected to Brian Mulroney’s in voters’ minds.

Berntson’s role in the GST implementation was about to cement that sentiment.

Born in 1941 in Oxbow, Saskatchewan, Berntson had spent most of the 1970s touring rural Saskatchewan convincing farmers that conservatives, not liberals, were the free market solution to their woes. Berntson was behind the grooming of Grant Devine for the leadership of the PC Party, as well as a number of the scandals that plagued it, including Gigatex.

In fact in his book Singing the Blues: The Conservatives in Saskatchewan, ultimate insider Dick Spencer said,

“Berntson, from the beginning of the Devine years, was the leader of the band in all matters, second only to the premier.”

Just under ten years after being appointed to Brian Mulroney’s senate, Eric Berntson would be tried and found guilty for stealing over $40,000 from Saskatchewan taxpayers, using multiple strategies, methods and fraudulent monikers.

That included the $8000 he requested from Scraba, right before Brian Mulroney appointed him to the senate.

As his top general defrauded Saskatchewan taxpayers, Grant Devine was preaching at them.

“People who live without God lose the basis for authority. Emotional, mental and spiritual health of children is best maintained in homes where parents love and care for each other. Teachers, coaches and friends are influential, but parents are the most important.”

So pontificated Grant Devine from the pulpit of Regina’s Westhill Park Baptist Church one autumn Sunday morning in late 1990.

It wasn’t the first time Devine had used his platform to impart his opinion on matters of morality and godliness. Two years prior, in response to Svend Robinson’s historical coming out as a sitting gay MP, Devine had told reporters that he placed “homosexuals” in the same category as “bank robbers”.

Love the sinner but hate the sin, etcetera.

Hearing that it was working for Lynda Haverstock, Devine had embarked on a two week listening tour of his own. He sat in coffee shops and town halls across rural Saskatchewan having relatable conversations with grease-stained, coveralled farmers about the stark realities facing their operations.

It didn’t go quite as well as planned, however. At one stop in Herbert, Saskatchewan, Devine was repeatedly interrupted as he attempted discuss the future, by voters demanding answers about his past handlings of Saskatchewan’s finances.

At a public meeting in Vonda, Saskatchewan, held in October 1990 by the Saskatoon board of trade, well-known business advocate Dale Botting highlighted Devine’s out of control spending as a major issue with his second term:

“The 1986 campaign was a public auction of taxpayers’ funds with no real consideration of the public’s ability to pay anything; Devine began his second term with a huge ball and chain tied to his leg and everything has been downhill since.”

In the previous four years, Saskatchewan’s population had once again dropped below one million people. Devine had more than doubled the debt, from $1.9-billion in 1986 to $4.6-billion in 1990. GDP was dropping and the average Saskatchewan taxpayer was on the hook for a lot more than they had been in 1986.

As an unseasonably cold autumn moved into fall, some wondered if Grant Devine’s government was attempting to orchestrate it’s own demise.

On November 13, 1990, Saskatchewan Finance Minister Lorne Hepworth held a grim news conference in the Legislature’s media room. Dramatically he intoned that Saskatchewan must pick its own poison in order to address the province’s fiscal misfortunes.

“I am asking people to come out and do jury duty for their province and their children’s future to ensure our Saskatchewan way of life is maintained and preserved.”

Hepworth warned incoming, drastic cost-saving measures would be ultimately chosen by residents at a series of public meetings, but could include the imposition of healthcare premiums or hospital closures. As he spoke, he knew his Cabinet colleagues, as well as a number of senior staffers, were livid about it.

With a looming and increasingly hopeless provincial election on the horizon, Hepworth’s fellow Cabinet Ministers and PC Party caucus had been clear: they had no appetite for defending any cuts at all, never mind deep ones. Devine told Hepworth to get on with setting the tone in the media anyway.

Devine’s back was in the corner and he knew it. There was no money. No more Crowns to carve up and auction off to the lowest bidder. Without another cash infusion and series of further concessions from Ottawa, Saskatchewan was at real risk of going into default on the global markets.

Saskatchewan’s credit rating would be in tatters. Third party management, likely by the federal government, would be required.

The humiliation would be thorough.

In late September 1990 Grant Devine’s Minister of Environment, Grant Hodges, told a conference on sustainable development in Regina that his government was looking to create an "Environmental Action Plan” to fully integrate consideration for the environment into all of the government’s decisions and plans.

This was rich coming from the party that steamrolled federal environmental laws to ensure construction on the Rafferty-Alameda dam would continue unabated. Which it did, despite constant legal setbacks in a battle of wills being waged between conservative politicians at multiple levels of government and Canadian federal court judges.

In mid-November, Saskatchewan Court of Queen’s Bench Justice Donald MacPherson squashed the federal government’s latest application for a stop work order. It was a game of legal whack-a-mole, with another court challenge popping up as soon as one was knocked down.

Directly across from the entrance to the small Saskatchewan town of Alameda, directly adjacent Highway 9, sits the 125 year old Tetzlaff house.

Squat and square, brothers Harold and Edward Tetzlaff referred to the house their grandparents built as their “fortress”, given its exterior walls were almost a meter thick. Comprised of two layers of fieldstones sandwiching a layer of sand, then another interior of plaster, the house had withstood everything the harsh prairie winters had thrown at it.

Harold and Ed had known hard work since they were children. After their father died when they were just teenagers, the brunt of the work on the farm fell to them. Ed was forced to leave his post-secondary education dream behind at Luther College in Regina, where he’d been studying post WWII. Harold was pulled out of public school for harvest, though Ed insisted he go back after it was finished.

Just a handful of years later, their mother died of complications that arose from an ankle surgery. She was only 47.